Ledi Sayādaw

Ledi Sayādaw

A Manual of the Requisites of Enlightenment

Bodhipakkhiya Dīpanī

Translated by U Sein Nyo Tun

Download the » PDF file (1.41 Mbytes) to print your own booklets.

Contents

Preface to this Edition • Editor’s Preface • Preface to the Second Edition • Translator’s Preface

Four Types of Capacity for Path Attainment • Three Types of Patient

Necessary Conditions of Practice • The Age of Noble Ones is Still Extant

Consequences of Having Only Good Conduct • Consequences of Having Only Knowledge

The Essential Point • Those Who Await the Next Buddha

Lost Opportunity to Attain the Seeds of Knowledge • Assiduous and Successful Practice

A Word of Advice and Warning • Wrong Teachings

The Requisites of Enlightenment

I. Bodhipakkhiya Dhammā • II. The Four Foundations of Mindfulness

III. The Four Right Efforts • IV. The Four Bases of Success

V. The Five Controlling Faculties • VI. The Five Powers

VII. The Seven Factors of Enlightenment • VIII. The Eight Path Factors

IX. How to Practise the Bodhipakkhiya Dhammā • X. The Heritage of the Sāsana

Preface to This Edition

Preface to This Edition

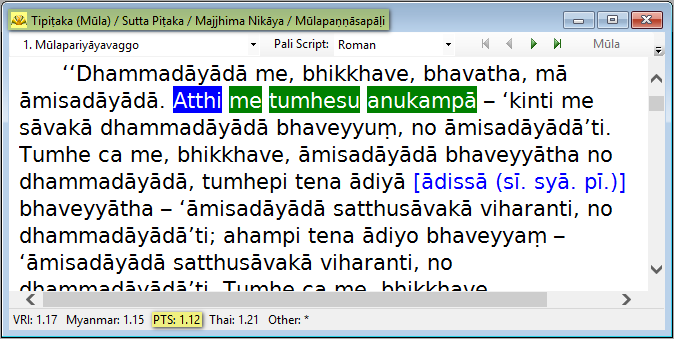

I have added Pāḷi diacritics to the online edition of the BPS while checking, that wherever quotations are used, they match the spellings used in the Pāḷi texts of the Chaṭṭha Saṅgāyana edition. There are some variant readings. The Sayādaw would have been familiar with the older edition from the fifth Saṅgāyana that is now housed in Mandalay, and known as The World’s Largest Book.

Words in bold dark blue text are quoted directly from the Pāḷi. This style of Nissaya, or word-by-word commentary, is common in discourses by Burmese Sayādaws.

I have made minor editions to the text, to modernise the language and make it gender neutral. The translation of saddhā is “faith” in some contexts and “confidence” in others. Initially, confidence in the teachings may waver, but when well-developed to the point of being a power or controlling faculty, it is steady and fully confident, since it is based on genuine insight and practical realisation.

A large part of the last section on the Heritage of the Sāsana is abridged in the BPS edition, so I have added this back from another source, and done my usual job of reducing the use of Pāḷi terms to make it easier for most to read and understand. The Simile of the Millionaire is also found in the Sayādaw’s Sāsana Dāyajja Dīpanī.

I have added an index (to the PDF Edition), which also replaces the glossary of Pāḷi words. I have removed some footnotes and added others, and added several hyperlinked cross-references to the Dictionary of Pāḷi Proper Names, the Dhammapada, and other quoted sources where available.

Editor’s Preface

Editor’s Preface

With the present volume we present to our readers another treatise by the eminent Burmese scholar-monk, the late Venerable Ledi Sayādaw, whose life sketch appears in a work of his, published earlier in this series, A Manual of Insight (Vipassanā Dīpanī).¹

We believe that this present treatise is one of the most helpful expositions of Dhamma which we have been privileged to publish in The Wheel series. It offers not only a wealth of information on many aspects of the Teaching, but is also a forcefully reasoned and stirring appeal to earnest endeavour towards the goal. We therefore wish to recommend this work to our readers’ close and repeated study and reflection.

This treatise has been reproduced from the journal The Light of the Dhamma (Rangoon), which regrettably has ceased publication. For permission of reprint we are grateful to the publishers, The Union of Burma Buddha’s dispensation Council, Rangoon.

In the present edition, many of the Pāḷi terms used in the original have been supplemented or replaced by the English equivalents, for facilitating the reading of the treatise. The last chapter has been condensed. Otherwise only minor changes have been made in the diction.

In the original publication, the term bodhipakkhiya-dhammā had been rendered by “factors leading to enlightenment,” which, however, resembles too closely the customary translation of the term bojjhaṅga by “factors of enlightenment” (see Section VII). Therefore the title of the treatise in the original translation and the rendering of the term in the body of the text have been changed into “Requisites of Enlightenment,” being one of the connotations of bodhipakkhiya-dhammā, as given in Section I. This nuance of meaning was chosen in view of the fact that this treatise does not deal with perfected constituents of enlightenment (bodhi) already achieved, but with the approach to that goal by earnest cultivation of those seven groups of qualities and practices that form the thirty-seven requisites of enlightenment.

A detailed table of contents and a comprehensive index have been added to this edition, for facilitating the use of this book.

Preface to the Second Edition

Preface to the Second Edition

This edition is extensively indexed for study. Its index includes both Pāḷi and English references. Moreover, a glossary has been added.

The Index refers to the English equivalents of the Pāḷi words and phrases. The Glossary lists the words both in English and in Pāḷi for easy reference. In some instances one English translation serves two Pāḷi words; in others, the opposite occurs. Note is made when this occurs.

Translator’s Preface

Translator’s Preface

The Venerable Ledi Sayādaw’s works are well-known in Burma. They are widely known because they are clear expositions of the Buddha Dhamma couched in language easily intelligible to an ordinary educated Burman. Yet, the Venerable Sayādaw’s works are not meant for an absolute beginner of Buddhist studies. There are many Buddhist technical terms that require a certain amount of previous foundation in Buddhist tradition and practice.

The Venerable Sayādaw’s exposition contains many technical Pāḷi terms that are used by him as if they were ordinary Burmese words. Many of these terms have been incorporated into the Burmese language either in their original Pāḷi form or with slight variations to accord with Burmese euphony. These are words that Burmans have made no attempt to translate, but have preferred to absorb them into the normal usage of the Burmese language. I have similarly made no attempt to translate many of them into English in the present translation. I have use these words in their original Pāḷi form, though in all such cases an attempt has been made to append short explanatory footnotes in order to facilitate continuity in reading.

Though the translation is not verbatim, yet a careful attempt has been made to render as nearly a verbatim translation as in possible in the circumstances, having regard to differences in the construction of sentences between English and Burmese, to differences in the manner of presentation and to the Venerable Sayādaw’s penchant for sometimes using extremely long sentences.

Many of the subheadings are not in the original text, but have been introduced by the translator for assisting the English reader.

The Venerable Sayādaw was a prolific writer. His works number over a hundred. Each of these works was written at the specific request of one or more of his numerous disciples, either as an answer to certain questions put to him, or, as in the present case, to expound certain important points or aspects of the Buddha-Dhamma.

Sein Nyo Tun

135, University Avenue,

Rangoon

A Manual of the Requisites of Enlightenment

A Manual of the Requisites of Enlightenment

Bodhipakkhiya Dīpanī

Introduction

In compliance with the request of the Pyinmana Myo-ok Maung Po Mya and Trader Maung Hla, during the month of Nayon, 1266 Burmese Era (June, 1904 C.E.), I shall state concisely the meaning and intent of the thirty-seven requisites of enlightenment (bodhipakkhiya-dhammā).

Four Types of Capacity for Path Attainment

It is stated in the Puggalapaññatti (Pug.16, the “Book of Classification of Individuals,” (p. 160) and in the Aṅguttaranikāya (A.ii.135) that, of the beings who encounter the Teaching of the Buddha (sāsana), four classes can be distinguished, viz:–

- Ugghaṭitaññū - One of quick understanding

- Vipañcitaññū - One who is clear-minded

- Neyya - One who can be taught

- Padaparama - One who can, at best, know only the word meaning

Of these four classes of beings, one of quick understanding (ugghaṭitaññū) is an individual who encounters a Buddha in person,² and who is capable of attaining the paths and fruits merely through hearing a short discourse.

A clear-minded individual (vipañcitaññū) is not capable of attaining the paths and fruits merely through hearing a short discourse, but is capable of attaining them when a short discourse is expounded at some length.

One who can be taught (neyya) is an individual who is not capable of attaining the paths and fruits through hearing a short discourse or when it is expounded at some length, but is one for whom it is necessary to study and take careful note of the sermon and the exposition, and then to practise the provisions contained therein for days, months, and years, in order to attain the paths and fruits.

This teachable class of individuals can be subdivided into many other classes according to the period of practice that each individual needs to attain the paths and fruits, and which further is dependent on the perfections (pāramī) that each has previously acquired, and the defilements (kilesā) that each has surmounted. These classes of individuals include, on the one hand, those for whom the necessary period of practice is seven days, and on the other, those for whom the necessary period of practice may extend to thirty or sixty years.

Further classes also arise, as for example in the case of individuals whose necessary period of practice is seven days; the stage of an Arahant may be attained if effort is made in the first or second period of life,³ while no more than the lower stages of the paths and the fruits can be attained if effort be made only in the third period of life.

Then, again, putting forth effort for seven days means exerting as much as is in one’s power to do so. If the effort is not of the highest order, the period of necessary effort becomes lengthened according to the laxity of the effort, and seven days may become seven years or longer.

If the effort during this life is not sufficiently intense as to enable one to attain the paths and the fruits, then release from worldly ills cannot be obtained during the present Buddha’s dispensation while release during future Buddha’s dispensations can be obtained only if the individual encounters them. No release can be obtained if no Buddha’s dispensation is encountered. It is only in the case of individuals who have secured a sure prediction (niyata-vyākaraṇa) made by a Buddha, that an encounter with a Buddha’s dispensation and release from worldly ills is certain. An individual who has not attained a sure prediction cannot be certain either of encountering a Buddha’s dispensation or achieving release from worldly ills, even though he has accumulated sufficient perfections to make both of these achievements possible.

These are considerations in respect of those individuals who possess the capabilities of attaining the paths and the fruits by putting forth effort for seven days, but who have not obtained sure prediction.

Similar considerations apply to the cases of those individuals who have the potential to attain the paths and the fruits by putting forth effort for fifteen days, or for longer periods.

One who can know the word meaning at best (padaparama) is an individual who, though encountering a Buddha’s dispensation, and though putting forth the utmost possible effort in both the study and practice of the Dhamma, cannot attain the paths and the fruits within this lifetime. All that he or she can do is accumulate good habits and potential (vāsanā).

Such a person cannot obtain release from worldly ills during this lifetime. If he or she dies while practising tranquillity (samatha) or insight (vipassanā) and attains rebirth either as a human being or a deity (deva) in the next existence, he or she can attain release from worldly ills in that existence within the present Buddha’s dispensation.

Thus did the Buddha declare with respect to four classes of individuals.

Three Types of Patient

In the same sources referred to above, the Buddha gave another classification of beings, dividing them into three classes resembling three types of sick persons,⁴ namely:–

- A person who is certain of regaining health in due time even though he does not take any medicine or treatment,

- A person who is certain of falling to make a recovery, and dying from the illness, no matter to what extent he may take medicines or treatment,

- A person who will recover if he takes the right medicine and treatment, but who will fail to recover and die if he fails to take the right medicine and treatment.

Persons who obtained the sure prediction from previous Buddhas, and who as such are certain of obtaining release from worldly ills in this life resemble the first class of sick persons.

A padaparama individual resembles the second class of sick persons. Just as this second class of sick person has no chance of recovery from his illness, a padaparama individual has no chance of obtaining release from worldly ills during this life. In future lives, however, he or she can obtain release either within the present Buddha’s dispensation or within future Buddha’s dispensations. The story of the youth Chattamāṇava,⁵ of the frog who became a deva,⁶ and of the ascetic Saccaka⁷ obtained release from worldly ills in following existences within the present Buddha’s dispensation.

A neyya class of individual resembles the third class of sick persons. Just as a person of this third class is related to the two ways of either recovering or dying from the sickness, so is a neyya individual related to the two eventualities of either obtaining release from worldly ills during the present life, or failing to obtain such release.

If such a neyya individual, knowing what is good for him according to his age, discards what should be discarded, searches for the right teacher, and obtains the right guidance from him and puts forth sufficient effort, he can obtain release from worldly ills in this very life. If, however, he becomes addicted to wrong views and wrong ways of conduct; if he finds himself unable to discard sensual pleasures; if although able to discard sensual pleasures he does not obtain the guidance of a good teacher; if he is unable to evoke sufficient effort; if although inclined to put forth effort he is unable to do so through old age; if although young he is liable to sickness; in all these cases he cannot obtain release from worldly ills in this present life. King Ajātasattu,⁸ the millionaire Mahādhana’s son,⁹ bhikkhu Sudinna,¹⁰ are cases of persons who could not obtain release from worldly ills in this present existence.

King Ajātasattu failed to obtain release because he had committed parricide. It is stated that he will drift in saṃsāra for two incalculable aeons (asaṅkhyeyya, 10¹⁴⁰ years) after which he will become a Solitary Buddha (Paccekabuddha).

The millionaire Mahādhana’s son indulged himself so excessively in sensual pleasures during his youth that he was unable to attain tranquillity of mind when he grew older. Far from obtaining release from worldly ills, he did not even get the opportunity of associating with the Triple Gem (tiratana).¹¹ Seeing his plight at that stage, the Buddha said to Ānanda: “Ānanda, if this millionaire’s son had become a bhikkhu in my sāsana during his youth or first period of his life, he would have become an Arahant and would have attained final cessation (parinibbāna)¹² in this present life. If, otherwise, he had become a bhikkhu during the second period of his life, he would have become a Non-returner (anāgāmi),¹³ and on death would have been reborn in the Suddhavāsa brahma-loka,¹⁴ whence he would attain final cessation. In the next alternative, if he had become a bhikkhu in my dispensation at the beginning of the third period of life, he would have become either a Once-returner (sakadāgāmi) or a Stream-winner (sotāpanna) and would have attained permanent release from rebirth in the lower realms¹⁵ (apāya).” Thus said the Buddha to the Venerable Ānanda. Thus, although he (the millionaire Mahādhana’s son) possessed perfections ripe enough to make his present life his last existence, not being a person who had secured a sure prediction, he failed to obtain release from worldly ills in his present life because of the upheavals caused by the defilements within him, and this is despite the fact that he had the opportunity of encountering the Buddha’s dispensation. If, further, his period of existence in the lower realms is prolonged because of evil acts done in this existence, he would not be able to rise again and emerge out of those lower realms in time for the dispensation of the future Metteyya Buddha. After that, the large number of world-cycles that follow are world-cycles where no Buddhas appear, there being no world-cycles within the vicinity of the present world where Buddhas are due to appear.¹⁶ Alas! Far indeed is this millionaire’s son from release from worldly ills even though he possessed perfections ripe enough to make his present existence his last one.

The general opinion current at the present day is that if the perfections are complete, one cannot miss encountering a Buddha’s dispensation even if one does not wish to do so, and that one’s release from worldly ills is ensured even though one may not desire such release. Those of this view fail to pay attention to the existence of one who has obtained a sure prediction made by a Buddha (niyata-vyākaraṇa) and one who has not obtained a sure prediction made by a Buddha. Considering the two texts from the Tipiṭaka mentioned above, and the story of the millionaire Mahādhana’s son it should be remembered that trainable individuals without a sure prediction (aniyata neyya) can attain release from worldly ills in this life only if they put forth sufficient effort, even if they possess perfections sufficient to enable them to obtain such release. If industry and effort are lacking, the paths and the fruits cannot be attained within the present Buddha’s dispensation.

Apart from these classes of persons, there are also an infinite number of other beings who, like the ascetics Āḷāra and Udaka (M.i.170), possess sufficient perfections for release from worldly ills, but who do not get the opportunity because they happen to be in one or the other of the eight inopportune places (aṭṭhakkhaṇā)¹⁷ where it is not possible to attain the paths and the fruits.

Necessary Conditions of Practice

Of the four classes of individuals mentioned, the ugghaṭitaññū classes can attain the path of Stream-winning and the other higher stages of wisdom — like Visākhā and Anāthapiṇḍika¹⁸ — through the mere hearing of a discourse. It is not necessary for such individuals to practise the Dhamma according to the stages of purification, such as purification of morality (sīla-visuddhi), of purification of mind (citta-visuddhi), and so on. Remember that this is also the case when deities attain release from worldly ills.

Hence it should be noted that the courses of practice such as purification of morality and mind, laid down in the Pāḷi Canon, are only for the neyya and padaparama classes of individuals before their attainment of the path of Stream-winning. These courses of practice are also for the first three classes of individuals prior to the achievement of the higher stages of the paths and the fruits. In the period after the attainment of Arahantship also, these courses of practice are used for the purpose of dwelling at ease in the present existence (diṭṭhadhamma-sukhavihāra),¹⁹ since Arahants have already gone through them.

After the passing of the first thousand years of the present Buddha’s dispensation, which constituted the times of Arahants possessing analytical knowledge (paṭisambhidā-ñāṇa), the period of the present Buddha’s dispensation comprises the times of the neyya and padaparama classes of individuals alone. At the present day, only these two classes of individuals remain.

An Individual Who Can Be Taught

Of these two classes of individuals, an individual of the neyya class can become a Stream-winner in this present life if he or she faithfully practises the bodhipakkhiya-dhammā comprising the four foundations of mindfulness (satipaṭṭhāna), four right efforts (sammappadhāna), etc. If lax in the practice, he or she can become a Stream-winner only in the next existence after being reborn in the deva planes. If he or she dies while still aloof from these requisites of enlightenment, he or she will become a total loss as far as the present Buddha’s dispensation is concerned, but can still attain release from worldly ills if encountering the dispensation of the next Buddha.

An Individual Who Can Know Only the Word Meaning

An individual of the padaparama class can attain release within this dispensation after rebirth in the celestial planes, if he or she can faithfully practise the requisites of enlightenment in the present existence.

The Age of Noble Ones is Still Extant

All of the five thousand years of this dispensation constitute the age of saints, which will continue as long as the Tipiṭaka remains in the world. Padaparama individuals have to use the opportunity afforded by encountering the present Buddha’s dispensation to accumulate as much of the seeds of perfections as they can within this lifetime. They have to accumulate the seeds of morality (sīla), concentration (samādhi), and wisdom (paññā).

Morality

Of these three kinds of accumulations — morality, concentration and wisdom — the seeds of morality means the five precepts (pañca-sīla),²⁰ eight precepts with right-livelihood as the eighth (ājīvaṭṭhamaka-sīla),²¹ eight precepts as observed on Uposatha days (aṭṭhaṅga-uposatha-sīla),²² ten precepts (dasaṅga-sīla),²³ in respect of laymen and women, and the monks’ morality (bhikkhu-sīla).²⁴

Concentration

The seeds of concentration are the efforts to achieve preparatory concentration (parikamma-samādhi) through one or other of the forty subjects of meditation, such as the ten meditation devices (kasiṇa), or, if further efforts can be evoked, the efforts to achieve access concentration (upacāra-samādhi), or, if still further efforts can be evoked, the efforts to achieve absorption concentration (appanā-samādhi).

Wisdom

The seeds of wisdom mean the cultivation of the ability to analyse the characteristics and qualities of material phenomena (rūpa), mental phenomena (nāma), the aggregates (khandhā), sense-faculties (āyatanā), elements (dhātu), truths (saccā), and dependent origination (paṭiccasamuppāda), as well as the cultivation of insight into the three characteristics (lakkhaṇa), namely, impermanence (anicca), unsatisfactoriness (dukkha), and not-self (anatta).

Of the three kinds of seeds of path-knowledge (magga-ñāṇa) and fruition-knowledge (phala-ñāṇa),²⁵ morality and concentration are like ornaments that permanently adorn the world and exist even in the empty world-cycles where no Buddhas arise. The seeds of morality and concentration can be obtained at will at any time. However, the seeds of wisdom, which are related to mind and matter, the aggregates, the sense faculties, the elements, the truths, and dependent origination can be obtained only when one encounters a Buddha’s dispensation. Outside of a Buddha’s dispensation one does not get the opportunity of even hearing the mere mention of words associated with wisdom, though an infinite number of empty world-cycles may have passed. Hence, those of the present era who are fortunate enough to be born into this world while a Buddha’s dispensation flourishes, if they intend to accumulate the seeds of path and fruition knowledge for the purpose of securing release from worldly ills in a future existence during a future Buddha’s dispensation, should pay special attention to the knowledge of ultimate realities (paramattha),²⁶ which is extremely difficult for one to come across, rather than trying to accumulate the seeds of morality and concentration. At the very least, they should attempt to gain insight into how the four great primaries (mahābhūta) — earth (pathavī), water (āpo), fire (tejo), and air (vāyo)²⁷ — constitute one’s body. If they acquire a good insight into the four primary elements, they obtain a sound collection of the seeds of wisdom, which are the most difficult to acquire, and this is so even though they may not acquire any knowledge of the other portions of the Abhidhamma. It can then be said that the difficult attainment of rebirth within a Buddha’s dispensation has been worthwhile.

Knowledge and Conduct

Knowledge and Conduct

Morality and concentration constitute conduct (caraṇa), while wisdom constitutes knowledge (vijjā). Thus are knowledge and conduct constituted. Knowledge resembles the eyes of a human being, while conduct resembles the limbs. Knowledge is like the eyes of a bird, while conduct is like its wings. A person who is endowed with morality and concentration, but lacks wisdom, is like one who possesses complete and whole limbs, but is blind in both eyes. A person who is endowed with knowledge but lacks conduct is like one who has good eyesight but is defective in his limbs. A person who is endowed with both knowledge and conduct is like a healthy person possessing both good eyesight and healthy limbs. A person who lacks both knowledge and conduct is like one defective in eyes and limbs, and is not worthy of being called a human being.

Consequences of Having Only Good Conduct

Amongst the persons living within the present Buddha’s dispensation, there are some who are fully endowed with morality and concentration, but do not possess the seeds of knowledge such as insight into the nature of material qualities, mental qualities, and the aggregates. Because they are strong in conduct they are likely to encounter the next Buddha’s dispensation, but because they lack the seeds of knowledge they cannot attain Enlightenment, even though they hear a discourse of the next Buddha in person. They are like Lāḷudāyī Thera,²⁸ Upananda Thera,²⁹ the notorious group of six monks, Chabbaggiyā,³⁰ and Pasenadi, the King of Kosala³¹ who all lived during the lifetime of the Omniscient Buddha. Because they were endowed with previously accumulated good conduct such as generosity and morality, they had the opportunity to associate with the Supreme Buddha, but since they lacked previously accumulated wisdom, the discourses of the Buddha, which they often heard throughout their lives, fell on deaf ears.

Consequences of Having Only Knowledge

There are others who are endowed with knowledge such as insight into the material and the mental qualities and the constituent groups of existence, but who lack conduct such as generosity (dāna), constant morality (nicca sīla), and morality observed on Uposatha days (uposatha-sīla). Should these persons get the opportunity of meeting and hearing the discourses of the next Buddha they can attain enlightenment because they possess knowledge, but since they lack conduct it would be extremely difficult for them to get the opportunity of meeting the next Buddha. This is so because there is an intervening world-cycle (antara-kappa) between the present Buddha’s dispensation and the next.

In those cases where these beings wander within the sensuous sphere during this period, it means a succession of an infinite number of existences and rebirths; in these cases an opportunity to meet the next Buddha can be secured only if all these rebirths are confined to the happy course of existence. If, in the interim, a rebirth occurs in one of the four lower regions, the opportunity to meet the next Buddha would be irretrievably lost, for one rebirth in one of the four lower worlds is often followed by an infinite number of further rebirths in one or other of them.

Those persons whose acts of generosity in this life are few, who are ill-guarded in their bodily acts, unrestrained in their speech, and unclean in their thoughts, and who thus are deficient in conduct, possess a strong tendency to be reborn in the four lower worlds when they die. If, through some good fortune, they manage to be reborn in the happy course of existence, wherever they may be reborn they are, because of their previous lack of conduct such as generosity, likely to be deficient in riches, and likely to meet with hardships, trials, and tribulations in their means of livelihood, and thus encounter tendencies to rebirth in the lower realms. Because of their lack of the conduct of constant morality, and Uposatha day morality, they are likely to meet with disputes, quarrels, anger and hatred in their dealings with others, in addition to being susceptible to diseases and ailments, and thus encounter tendencies towards rebirth in the lower realms. Thus will they encounter painful experiences in every existence, gathering undesirable tendencies, leading to the curtailment of their period of existence in the happy course of existence and causing rebirth in the four lower worlds. In this way, the chances of those who lack conduct for meeting the next Buddha are very slim indeed.

The Essential Point

In short, the essential fact is, only when one is endowed with the seeds of both knowledge and conduct can one obtain release from worldly ills in one’s next existence. If one possesses the seeds of knowledge alone, and lacks the seeds of conduct such as generosity and morality, one will fail to secure the opportunity of meeting the next Buddha’s dispensation. If, on the other hand, one possesses the seeds of conduct, but lacks the seeds of knowledge, one cannot attain release from worldly ills even though one encounters the next Buddha’s dispensation. Hence, those padaparama individuals of today, be they men or women, who look forward to meeting the next Buddha’s dispensation, should attempt to accumulate within the present Buddha’s dispensation the seeds of conduct by the practice of generosity, morality, and tranquillity meditation, and should also, at the very least, with respect to knowledge, try to gain insight into the four great primaries and thus ensure meeting the next Buddha’s dispensation, and having met it, to attain release from worldly ills.

When it is said that generosity is conduct, it comes under the category of confidence (saddhā), which is one of the seven attributes of good people (saddhamma), which again comes under the fifteen kinds of good conduct (caraṇa-dhammā). The fifteen are:–

- Morality (sīla),

- Sense-faculty restraint (indriya-saṃvara),

- Moderation in eating (bhojane mattaññutā),

- Devotion to wakefulness (jāgariyānuyoga),

- to 11. The seven attributes of good people (saddhammā),

12. to 15. The four absorptions (jhāna).

These fifteen qualities are possessed by the highest attainer of absorption (jhāna-lābhī). So far as those individuals practising insight only (sukkha-vipassaka) are concerned, they should possess eleven of them, i.e., without the four absorptions (jhāna).

For those who look forward to meeting the next Buddha’s dispensation, generosity, morality of the Uposatha, and the seven attributes of good people are essential.

Those who wish to attain the paths and the fruits in this very life must fulfil the first eleven, i.e., morality, sense-faculty restraint, moderation in eating, wakefulness, and the seven attributes of good people. Herein, morality means the permanent practice of morality ending with right-livelihood (ājīvaṭṭhamaka-nicca-sīla) and sense-faculty restraint means guarding the six sense-doors — the eyes, ears, nose, tongue, body and mind. Moderation in eating means taking just sufficient food to preserve the health of the body and being satisfied with that. Devotion to wakefulness means not sleeping during the day, sleeping only during one of the three watches of the night, and practising meditation during the other two periods.

The seven attributes of good people (saddhamma) are:–

- Confidence (saddhā),

- Mindfulness (sati),

- Shame of wrong-doing (hirī),

- Fear of wrong-doing (ottappa),

- Great learning (bāhusacca),

- Energy (viriya),

- Wisdom (paññā).

For those who wish to become Stream-winners during this life there is no special necessity to practise generosity. However, let those who find themselves unable to evoke sufficient effort towards acquiring the ability to obtain release from worldly ills during the present Buddha’s dispensation make special attempts to practise generosity and morality on Uposatha days.

Those Who Await the Next Buddha

Since the work in the case of those who depend on and await the next Buddha consists of no more than acquiring accumulation of perfections, it is not strictly necessary for them to adhere to the stages of practice laid down in the Pāḷi texts, viz: morality, concentration, and wisdom. They should not thus defer the practice of concentration before the completion of the practice of morality, or defer the practice of wisdom before the completion of the practice of concentration. In accordance with the order of the seven purifications — 1) purification of morality (sīla-visuddhi), 2) purification of mind (cittavisuddhi), 3) purification of view (diṭṭhi-visuddhi), 4) purification by overcoming doubt (kaṅkhāvitaraṇa-visuddhi), 5) purification by knowledge and vision of what is path and not path (maggāmagga-ñāṇadassana-visuddhi), 6) purification by knowledge and vision of the course of practice (paṭipadā-ñāṇadassana-visuddhi), and 7) purification by knowledge and vision (ñāṇadassana-visuddhi), they should not postpone the practice of any course of purification until the completion of the respective previous course. Since they are engaged in the accumulation of as much of the seeds of perfections as they can, they should contrive to accumulate as much morality, concentration, and wisdom as lies in their power.

When it is stated in the Pāḷi texts that purification of mind should be practised only after the completion of the practice of purification of morality, that purification of view should be practised only after the completion of the practice of purification of mind, that purification by overcoming doubt should be practised only after the completion of the practice of purification of view, that the work of contemplating impermanence, unsatisfactoriness, and not-self) should be undertaken only after the completion of the practice of purification by overcoming doubt — the order of practice prescribed is meant for those who attempt the speedy realisation of the paths and fruits in this very life. Since those who find themselves unable to call forth such effort, are engaged only in the accumulation of the seeds of perfections, are occupied in gaining whatever they can of good practices, it should not be said in their case that the practice of purification of mind consisting of advertence of the mind to tranquillity should not be undertaken before the fulfilment of purification of morality.

Even in the case of hunters and fishermen, it should not be said that they should not practise tranquillity and insight meditation unless they discard their livelihood. One who says so causes an obstruction to the dhamma (dhammantarāya). Hunters and fishermen should be encouraged to contemplate the noble qualities of the Buddha, Dhamma, and Saṅgha. They should be induced to contemplate, as much as is within their power, the characteristic of loathsomeness in one’s body. They should be urged to contemplate the liability of oneself and all creatures to death. I have come across the case of a leading fisherman who, as a result of such encouragement, could repeat fluently from memory the Pāḷi text and word-for-word translation (nissaya) of the Abhidhammatthasaṅgaha, and the Paccaya Niddesa of the Book of Relations (Paṭṭhāna), while still following the profession of a fisherman. These accomplishments constitute very good foundations for the acquisition of knowledge.

At the present time, whenever I meet my lay supporters (dāyaka), I tell them, in the true tradition of a bhikkhu, that even though they are hunters and fishermen by profession, they should be ever mindful of the noble qualities of the Triple Gem and the three characteristics of existence. To be mindful of the noble qualities of the Triple Gem constitutes the seed of conduct. To be mindful of the three characteristics of existence constitutes the seed of knowledge. Even hunters and fishermen should be encouraged to practise such advertence of mind. They should not be told that it is improper for hunters and fishermen to practise advertence of mind towards tranquillity and insight. They should be helped towards better understanding, should they be in difficulties. They should be urged and encouraged to keep on trying. They are at that stage when even the work of accumulating perfections and good tendencies is to be extolled.

Lost Opportunity to Attain the Seeds of Knowledge

Some teachers, who are only aware of the existence of direct and unequivocal statements in the Pāḷi texts regarding the order of practice of the seven purifications, but who take no account of the value of the present era, say that in the practices of tranquillity and insight no results can be achieved unless purification of morality is first fulfilled, however intense the effort may be. Some misinformed ordinary people are beguiled by such statements. Thus an obstruction to the dhamma has occurred.

Because they do not know the value of the present era, they will lose the opportunity to attain the seeds of knowledge, which are attainable only when a Buddha’s dispensation is encountered. In truth, they have not yet attained release from worldly ills and are still drifting in saṃsāra because, though they have occasionally encountered dispensations of Buddhas in the inconceivably long saṃsāra, where Buddha’s dispensations more numerous than the grains of sands on the banks of the Ganges have appeared, they did not acquire the foundation of the seeds of knowledge.

When seeds are spoken of, there are seeds ripe or mature enough to sprout into healthy and strong seedlings, and there are many degrees of ripeness or maturity. There are also seeds that are unripe or immature. People who do not know the meaning of the passages they recite, or who do not know the right methods of practice, or even though they know the meaning, and customarily read, recite, and count their beads while performing the work of contemplating the noble qualities of the Buddha and the three characteristics, possess seeds that are unripe and immature. These unripe seeds may be ripened and matured by the continuation of such work in the existences that follow, if an opportunity for such continued work occurs.

The practice of tranquillity until the appearance of the preparatory sign (parikamma-nimitta)³² and the practice of insight (vipassanā) until insight is obtained into mind and matter even once, are mature seeds filled with pith and substance. The practice of tranquillity until the appearance of the acquired image (uggaha-nimitta)³³ and the practice of insight meditation until the acquisition of knowledge of comprehension (sammāsana-ñāṇa)³⁴ even once, are seeds that are still more mature. The practice of tranquillity until the appearance of the counterpart image (paṭibhāga-nimitta),³⁵ and the practice of insight meditation until the occurrence of the knowledge of arising and passing away (udayabbaya-ñāṇa) ³⁶ even once, are seeds that are yet more highly mature. If further efforts can be made in both tranquillity and insight meditation, still more mature seeds can obtained, bringing great benefit.

Assiduous and Successful Practice

When it is said in the Pāḷi texts that only when there has been preparation (adhikāra) in previous Buddha’s dispensations, can the corresponding absorptions, paths, and fruits be obtained in the following Buddha’s dispensations. Thus the word preparation means planting successful seeds. Those who pass their lives with traditional practices that are just imitation tranquillity meditation and imitation insight meditation do not come within the purview of those who possess the seeds of tranquillity and insight that can be called preparation.

Of the two kinds of seeds, those who encounter a Buddha’s dispensation, but who fail to acquire the seeds of knowledge, suffer a grave loss indeed. This is so because the seeds of knowledge that are related to mental and physical phenomena can only be obtained within a Buddha’s dispensation, and that only when one is sensible enough to secure them. Hence, in the present era, those who find themselves unable to contemplate and investigate at length into the nature of mental and physical phenomena should, throughout their lives, undertake the task of committing the four great primaries to memory, then contemplating their meaning and discussing them, and lastly seeking insight into how they are constituted in their bodies.

Here ends the part showing, by a discussion of four classes of individuals and three kinds of individuals as given in the Sutta and Abhidhamma, that:–

- Those who within the Buddha’s dispensation do not practise tranquillity and insight meditation, but allow the time to pass with imitations, suffer great loss as they fail to use the unique opportunity arising from their existence as human beings within a Buddha’s dispensation;

- This being the time of padaparama and neyya classes of individuals, if they heedfully put forth effort, they can secure ripe and mature seeds of tranquillity and insight, and easily attain the supramundane benefit either within this life or in the celestial realms in the next life — within this Buddha’s dispensation or within that of the next Buddha;

- They can derive immense benefit from their existence as human beings during the Buddha’s dispensation.

Here ends the exposition of the three kinds of patient and the four kinds of individuals.

A Word of Advice and Warning

If the Tipiṭaka, which contains the discourses of the Buddha delivered during forty-five rainy seasons (vassa), be condensed and the essentials extracted, the thirty-seven requisites of enlightenment are obtained. These thirty-seven constitute the essence of the Tipiṭaka. If these be further condensed, the seven purifications are obtained. If again the seven purifications be condensed, they become morality, concentration, and wisdom. These are called the dispensation of higher morality (adhisīla-sāsana), the dispensation of higher concentration (adhicitta-sāsana), and the dispensation of higher wisdom (adhipaññā-sāsana). They are also called the three trainings (sikkhā).

When morality is mentioned, the essential for laymen is constant morality. Those people who fulfil constant morality become endowed with conduct which, with knowledge, enables them to attain the paths and the fruits. If these individuals can add the refinement of morality observed on Uposatha days over constant morality, it is much better. For laymen, constant morality means eight precepts with right-livelihood as the eighth (ājīvaṭṭhamaka-sīla). That morality must be properly and faithfully kept. If, because they are ordinary persons (puthujjana) they break the morality, it can be re-established immediately by renewing the undertaking to keep it for the rest of their lives. If, on a future occasion, the morality is again broken, it can again be similarly cleansed, and every time this cleansing occurs, the person concerned again becomes endowed with morality. The effort is not difficult. Whenever constant morality is broken, it should be immediately re-established. In these days, many people are endowed with such morality.

However, those who have attained perfect concentration in one or another of the meditation exercises, or in the practice of meditation on loathsomeness (asubha-bhāvanā), etc., or who have attained insight into mental and physical phenomena, the three characteristics, etc., are very rare because these are times when wrong teachings (micchā-dhamma) are ripe that are likely to cause an obstruction to the dhamma.

Wrong Teachings

By wrong teachings likely to cause obstruction to the Dhamma are meant such views, practices, and limitations as the inability to see the dangers of saṃsāra, the belief that these are times when the paths and the fruits can no longer be attained, the tendency to defer effort until the perfections ripen, the belief that persons of the present day are reborn with only two wholesome roots (dvihetuka paṭisandhi),³⁷ the belief that the great teachers of the past did not existent, etc.

Even though it does not reach the ultimate, no wholesome kamma is ever futile. If an effort is made, wholesome kamma is instrumental in cultivating perfections in those who do not yet possess them. If no effort is made, the opportunity to acquire perfections is lost. If those whose perfections are immature put forth effort, their perfections become ripe and mature. Such individuals can attain the paths and fruits in their next existence within the present Buddha’s dispensation. If no effort is made, the opportunity for the perfections to ripen is lost. If those whose perfections are ripe and mature put forth effort, the paths and the fruits can be attained in this life. If no effort be made, the opportunity to attain the paths and the fruits is lost.

If those who were reborn with only two wholesome roots put forth effort, they can be reborn with three wholesome roots (tihetuka-paṭisandhi)³⁸ in their next existence. If they do not put forth effort, they cannot ascend from the stage of two wholesome roots and will slide down to the stage of having no wholesome roots (ahetuka).³⁹ Suppose there is a certain person who plans to become a bhikkhu. If another person says to him, “Entertain the intention only if you can remain a monk for your whole life. Otherwise do not entertain the idea”—this would amount to causing an obstruction to the dhamma.

The Buddha said: “Cittuppādampi kho ahaṃ, Cunda, kusalesu dhammesu bahukāraṃ vadāmi, ko pana vādo kāyena vācāya anuvidhīyanāsu! I declare, Cunda, that the mere arising of an intention of performing good deeds is productive of great benefit, so what needs to be said regarding wholesome actions by body or speech‽” (M.i.43).

To disparage either the act of generosity (alms-giving) or to discourage the performer of generosity, may cause an obstruction to merit (puññāntarāya). If acts of morality, concentration, and wisdom, or those who perform them are disparaged, an obstruction to the dhamma may be caused. If an obstruction to meritorious deeds is caused, one is liable to be bereft of power and influence, of property and riches, and to be abjectly poor in the lives that follow. If an obstruction to the dhamma is caused, one is liable to be defective in conduct and behaviour and defective of knowledge, and thus be utterly low and debased in the existences that follow. Hence, let all beware!

Here ends the section showing how the rare opportunity of rebirth as a human being can be made worthwhile, by ridding oneself of the faults mentioned above, and putting forth effort in this life to close the gates of the four lower realms in one’s future round of rebirths, or to accumulate the seeds that will enable one to attain release from worldly ills in the next existence or within the next Buddha’s dispensation, through the practice of tranquillity and insight meditation, with resolution, zeal, and diligence.

The Requisites of Enlightenment

The Requisites of Enlightenment

I. Bodhipakkhiya Dhammā

I shall now concisely describe the thirty-seven requisites of enlightenment,⁴⁰ which should be practised with energy and determination by those who wish to cultivate tranquillity and insight, thus making the rare opportunity of human rebirth in the present Buddha’s dispensation worthwhile.

The requisites of enlightenment consist of thirty-seven factors in seven groups:–

- Four foundations of mindfulness (satipaṭṭhāna),

- Four right efforts (sammappadhāna),

- Four bases of success (iddhipāda),

- Five controlling faculties (indriya),

- Five powers (bala),

- Seven factors of enlightenment (bojjhaṅga),

- Eight path factors (maggaṅga).

The bodhipakkhiya-dhammā are so called because they form part (pakkhiya) of enlightenment or awakening (bodhi), which here refers to the knowledge of the paths (magga-ñāṇa). They are mental phenomena (dhammā) with the function of being proximate causes (padaṭṭhāna), requisite ingredients (sambhāra) and bases, or sufficient conditions (upanissaya), of path knowledge (magga-ñāṇa).

II. The Four Foundations of Mindfulness

II. The Four Foundations of Mindfulness

The word satipaṭṭhāna is defined as follows:

“Bhusaṃ tiṭṭhati’ti paṭṭhānaṃ satipaṭṭhānaṃ.”

This means: “What is firmly established is a foundation; mindfulness itself is such a foundation.”

There are four foundations of mindfulness:–

- Contemplation of the body as a foundation of mindfulness (kāyānupassanā-satipaṭṭhāna),

- Contemplation of feelings as a foundation of mindfulness (vedanānupassanā-satipaṭṭhāna),

- Contemplation of the mind as a foundation of mindfulness (cittānupassanā-satipaṭṭhāna),

- Contemplation of mind-objects as a foundation of mindfulness (dhammānupassanā-satipaṭṭhāna).

- Kāyānupassanā-satipaṭṭhāna means mindfulness that is firmly established on bodily phenomena, such as inhalation and exhalation.

- Vedanānupassanā-satipaṭṭhāna means mindfulness that is firmly established on feelings or sensations.

- Cittānupassanā-satipaṭṭhāna means mindfulness that is firmly established on thoughts or mental processes, such as thoughts associated with passion or dissociated from passion.

- Dhammānupassanā-satipaṭṭhāna means mindfulness that is firmly established on phenomena such as the hindrances (nīvaraṇa).

Of the four, if mindfulness or attention is firmly established on a part of the body, such as on respiration, it is tantamount to attention being firmly established on all things. This is because the ability to place one’s attention on any object at will has been acquired. “Firmly established” means, if one desires to place the attention on the respiration for an hour, one’s attention remains firmly fixed on it for that period. If one wishes to do so for two hours, one’s attention remains firmly fixed on it for two hours. There is no occasion when the attention becomes released from its object on account of the instability of initial application (vitakka).

For a detailed account see the Satipaṭṭhāna Sutta.⁴¹

Why is it incumbent on us to firmly establish the mind without fail on any object such as the respiration? It is because we need to gather and control the six types of consciousness (viññāṇa),⁴² which have been drifting tempestuously and untrained throughout the past inconceivably long and beginningless saṃsāra.

I shall make it clearer. The mind tends to flit about from one to another of the six sense objects, which lie at the approaches to the six sense-doors.⁴³

The Simile of the Madman

As an example, take the case of a madman who has no control over his mind. He does not even know the mealtime, and wanders about aimlessly from place to place. His parents look for him and give him his meal. After eating five or six morsels of food he overturns the dish and walks away. He thus fails to get a square meal. To this extent he has lost control of his mind. He cannot control his mind even to the extent of finishing the business of eating a meal. In talking, he cannot control his mind to the extent of finishing a sentence. The beginning, the middle, and the end do not agree with one another. His speech has no meaning. He cannot be of use in any undertaking worldly undertaking. He is unable to perform any task. Such a person can no longer be classed as a normal human being, and so has to be ignored.

This madman becomes a sane and normal person again, if he meets a good doctor and the doctor applies a cure. Thus cured he obtains control of his mind in the matter of taking his meals, and can now eat his fill. He has control over his mind in all other matters as well. He can perform his tasks till they are completed, just like others. Just like others, he can also complete his sentences. This is an example.

In this world, persons who are not insane but who are normal and have control over their minds, resemble such a mad person who has no control over his mind when it comes to the matter of tranquillity and insight. Just as the madman upsets the food dish and walks away after five or six morsels of food, although he attempts to eat his meal, these normally sane persons find their attention wandering because they have no control over their minds. Whenever they pay respects to the Buddha and contemplate his noble qualities, they do not succeed in keeping their minds fixed on those noble qualities, but find their attention being diverted many times to other objects of thought, and thus they even fail to reach the end of “Iti pi so Bhagava” — “Thus indeed is this Blessed One …”

It is as if a man suffering from hydrophobia who seeks water feverishly with parched lips, runs away from it with fear when he sees a lake of cool refreshing water. It is also like a diseased man who, when given a diet of relishing food replete with medicinal qualities, finds the food bitter to his taste and, unable to swallow it, is obliged to spit and vomit it out. In just the same way, these persons find themselves unable to approach the contemplation of the noble qualities of the Buddha effectively, and cannot maintain dwelling on them.

In reciting “Iti pi so Bhagava” if their recitation is interrupted every time their minds wander, and if they have to start afresh from the beginning every time such an interruption occurs, they would never reach the end of the text even though they keep on reciting for a whole day, a whole month, or a whole year. At present they manage to reach the end because they can keep on reciting from memory even though their minds wander elsewhere.

In the same way, there are those who, on Uposatha days, plan to go to quiet places to contemplate the thirty-two parts of the body, such as head hairs (kesa), body hairs (loma), etc., or the noble qualities of the Buddha, but who ultimately end up in the company of friends and associates because they have no control over their minds, and because of the upheavals in their thoughts and intentions. When they take part in group recitations, although they attempt to direct their minds to tranquillity meditation on the sublime abidings (brahmavihāra),⁴⁴ such as reciting the formula for diffusing loving-kindness (mettā), because they have no control over their minds, their thoughts are not concentrated, but are scattered aimlessly, and they end up only with the external manifestation of the recitation.

These facts are sufficient to show how many people resemble the insane while performing wholesome deeds.

“Pāpasmiṃ ramatī mano — The mind takes delight in evil.” (Dhp v 116)

Just as water naturally flows down from high places to low places, the minds of beings, if left uncontrolled, naturally approaches evil. This is the tendency of the mind.

I shall now draw, with examples, a comparison between those who exercise no control over their minds and the insane person mentioned above.

The Simile of the Boatman

There is a river with a swift current. A boatman who is unfamiliar with the control of the rudder, drifts down the river with the current. His boat is loaded with valuable merchandise for trading and selling at the towns on the lower reaches of the river. As he drifts down, he passes stretches of the river lined with mountains and forests where there are no harbours or anchorages for his boat. He thus continues to drift down without stopping. When night descends, he passes towns and village with harbours and anchorages, but he does not see them in the darkness of the night, and thus he continues to drift without stopping. When daylight arrives, he comes to places with towns and villages, but not having any control over the rudder of the boat, he cannot steer it to the harbours and anchorages, and thus, inevitably, he continues to drift down until he reaches the great wide ocean.

The infinitely lengthy saṃsāra is like the swift-flowing river. Beings having no control over their minds are like the boatman who is unable to steer his boat. The mind is like the boat. Beings who have drifted from one existence to another in the empty world-cycles where no Buddhas appear, are like the boatman drifting down those stretches of the river lined by mountains and forests, where there are no harbours and anchorages. Sometimes these beings are born in world-cycles where a Buddha’s dispensation flourishes, but are oblivious to them because they happen to be in one or other of the eight inopportune situations. They resemble the boatman who drifts down stretches of the river lined by towns and villages with harbours and anchorages, but does not see them because it is night. When, at other times, they are born as human beings, devas or Brahmas, within a Buddha’s dispensation, but fail to secure the paths and the fruits because they are unable to control their minds and put forth effort to practise the insight meditation exercises of the four foundations of mindfulness thus continuing still to drift in saṃsāra, they resemble the boatman who sees the banks lined by towns and villages with harbours and anchorages, but is unable to steer towards them because of his inability to control the rudder, and thus continues inevitably to drift down towards the ocean.

In the infinitely lengthy saṃsāra, those beings who have obtained release from worldly ills within the dispensations of the Buddhas who have appeared, whose numbers exceed the grains of sand on the banks of the river Ganges, are beings who had control over their minds and who possessed the ability of sustaining their attention on any desired object at will through the practice of the foundations of mindfulness.

This shows the trend of the wandering in the course of existence of those beings who do not practise the foundations of mindfulness, even though they are aware of the fact that they have no control over their minds when it comes to the practice of tranquillity and insight.

The Simile of the Training of Bullocks

Comparisons may also be made with the taming and training of bullocks for the purpose of yoking them to ploughs and carts, and to the taming and training of elephants for employment in the service of the king, or on battlefields.

In the case of the bullock, the young calf has to be regularly herded and kept in a cattle-pen, then a nose rope is passed through its nostrils and it is tied to a post and trained to respond to the rope’s control. It is then trained to submit to the yoke, and only when it becomes amenable to the yoke’s burden is it put to use for ploughing and drawing carts and thus effectively employed to trade and profit. This is the example of the bullock.

In this example, just as the owner’s profit and success depends on the employment of the bullock in the drawing of ploughs and carts after training it to become amenable to the yoke, so does the true benefit of lay persons and bhikkhus within the present Buddha’s dispensation depend on training in tranquillity and insight meditation.

In the present Buddha’s dispensation, the practice of purification of morality (sīla-visuddhi) resembles the training of the young calf by herding it and keeping it in cattle-pens. Just as, if the young calf is not herded and kept in cattle-pens, it would damage and destroy the property of others and thus bring liability on the owner, so too, if a person lacks purification of morality, the three kinds of unwholesome kamma⁴⁵ would run riot, and the person concerned would become subject to worldly ills and to the evil results indicated in the Dhamma.

The efforts to develop mindfulness of the body (kāyagata-sati) resembles the passing of the nose-rope through the nostrils and training the calf to respond to the rope after tying it to a post. Just as when a calf is tied to a post it can be kept wherever the owner desires it to be, and it cannot run loose, so when the mind is tied to the body with the rope of mindfulness, that mind cannot wander freely, but is obliged to remain wherever the owner desires it to be. The habits of a disturbed and distracted mind acquired during the inconceivably long saṃsāra, become weakened.

A person who performs the practice of tranquillity and insight without first attempting body contemplation, resembles the owner who yokes the still untamed bullock to the cart or plough without the nose-rope. Such an owner would find himself unable to control the bullock as he wishes. Because the bullock is wild, and because it has no nose-rope, it will either try to run off the road, or escape by breaking the yoke.

On the other hand, a person who first tranquillises and trains the mind with body contemplation before turning the mind to the practice of tranquillity and insight meditation will find that attention will remain steady and the work will be successful.

The Simile of the Wild Elephant

In the case of the elephant, the wild elephant has first to be brought out from the forest into the field hitched on to a tame, well-trained elephant. Then it is taken to a stockade and tied up securely until it is tamed. When it thus becomes absolutely tame and quiet, it is trained in the various kinds of work in which it will be employed in the service of the king. It is only then that it is used in state functions and on battlefields.

The realm of sensual pleasures resembles the forest where the wild elephant enjoys himself. The Buddha’s dispensation resembles the open field into which the wild elephant is first brought out. The mind resembles the wild elephant. Confidence (saddhā) and will (chanda) in the teachings of the Buddha resemble the tame, trained elephant to which the wild elephant is hitched and brought out into the open. purification of morality resembles the stockade. The body, or parts of the body, such as respiration resemble the post in the stockade to which the elephant is tied. Mindfulness of the body resembles the rope by which the wild elephant is tied to the post. The preparatory work towards tranquillity and insight resembles the preparatory training of the elephant. The work of tranquillity and insight resembles the king’s parade ground or the battlefield. Other points of comparison can also be easily recognised.

Thus I have shown by the examples of the mad man, the boatman, the bullock, and the wild elephant, the main points of body contemplation, which is by ancient tradition the first step that has to be undertaken in the work of proceeding onwards from purification of morality within the dispensations of all the Buddhas who have appeared in the inconceivably long saṃsāra.

The essential meaning is that, whether it be by mindfulness of respiration (ānāpānasati), or by awareness of the four postures: going, standing, sitting, lying down (iriyāpatha), or by clear comprehension of all activities (sampajañña) or by attention to the elements (dhātu-manasikāra), or by perception of bones (aṭṭhika-saññā), one strives to acquire the ability of placing one’s attention on one’s body and its postures for as long as one wishes throughout the day and night as long as one is awake. If one can keep one’s attention fixed for as long as one wishes, then mastery has been obtained over one’s mind. Thus one attains release from the state of a mad man. One now resembles the boatman who has obtained mastery over his rudder, or the owner of the tamed and trained bullock, or the king who employs the tamed and trained elephant.

There are many kinds, and many grades, of mastery over the mind. The successful practice of body contemplation is, in the Buddha’s dispensation, the first stage of mastery over one’s mind.

Those who do not wish to follow the way of tranquillity, but who wish to pursue the path of pure insight (sukkha-vipassaka), should proceed straight to insight after the successful establishment of body contemplation.

If they do not want to practise body contemplation separately, but intend to practise insight with such industry that it carries body contemplation with it, they will succeed, provided that they really have the necessary wisdom and industry. The body contemplation that is associated with knowledge of arising and passing away (udayabbaya-ñāṇa), which clearly sees phenomena coming into existence and passing away, is very valuable indeed.

In the tranquillity method, by practising the body contemplation of respiration, one can attain up to the fourth absorption of the form sphere (catuttha rūpavacara jhāna); by practising attention to the appearance (vaṇṇa-manasikāra) of the thirty-two parts of the body, such as body hairs, head hairs, etc., one can gain all eight attainments (samāpatti),⁴⁶ and by practising contemplation of loathsomeness (paṭikkūla-manasikāra) of the same body contemplation one can attain the first absorption. If insight is attained in the process, one can also attain the paths and the fruits.

Even if completion is not arrived at in the practice of tranquillity and insight, if the stage is reached where one attains control over one’s mind and the ability to keep one’s attention fixed on wherever one wishes it to be, it was said by the Buddha that one can be said to enjoy the taste of the deathless (amata), i.e., nibbāna.

“Amataṃ tesaṃ, bhikkhave, paribhuttaṃ yesaṃ kāyagatāsati paribhuttā”ti. (A.i.45)

“Those who practice body contemplation, taste the deathless.”

Here, the deathless means great mental peace.⁴⁷

In its original untamed state, the mind is highly unstable in its attentiveness, and thus is parched and hot in nature. Just as the insects that live on capsicum are not aware of its heat, just as beings pursuing the realm of craving (taṇhā) are not aware of its heat, just as beings subject to anger and pride are not aware of the heat of pride and anger, so are beings unaware of the heat of unsettled minds. It is only when, through mindfulness of the body, the unsettled condition of the mind disappears, that they become aware of the heat of an unsettled mind. Having attained the state of the disappearance of that heat, they develop a fear of relapsing to that heat. The case of those who have attained the first absorption, or knowledge of arising and passing away through body contemplation, needs no elaboration.

Hence, the higher the attainments that one reaches, the more difficult does it become for one to be apart from mindfulness of the body. The Noble Ones use the four foundations of mindfulness as mental nutriment until they attain final cessation (parinibbāna).

The ability to keep one’s attention fixed on the body, such as on the respiration, for one or two hours takes one to the culmination of one’s work in seven days, or fifteen days, or a month, or two months, or three months, or four months, or five months, or six months, or a year, or two years, or four years, according to the intensity of one’s efforts. For the method of practising mindfulness of respiration, see my Ānāpāna Dīpanī.⁴⁸

There are many books by past teachers on the method of the thirty-two parts of the body. In this method, head hair (kesa), body hair (loma), nails (nakha), teeth (danta), skin (taco), are the group ending with skin as the fifth (taca-pañcaka). If attention can be firmly fixed on these five, the work of body contemplation is accomplished.

For analysis of the four great primaries (catudhātuvavatthāna), contemplation of physical phenomena (rūpa-vipassanā), and contemplation of mental phenomena (nāma-vipassanā), see my Lakkhaṇa Dīpanī, Vijjāmagga Dīpanī, Āhāra Dīpanī and Anatta Dīpanī.⁴⁹

Here ends a concise explanation of body contemplation, which is one of the four foundations of mindfulness, and which has to be established first in the work of mental development (bhāvanā) by individuals who can be taught (neyya) and those who can, at best, only know the word meaning (padaparama), for the purpose of attaining the paths and the fruits within a Buddha’s dispensation.

III. The Four Right Efforts

III. The Four Right Efforts

The word sammappadhāna is defined as follows:

“Bhusaṃ dahati vahati’ti padhānaṃ sammādeva padhānaṃ sammappadhānam.”

This means: padhāna is an effort carried out strongly, intensively; if carried out properly, rightly, it is sammappadhāna, right effort.

It is an effort that has not in it any element of unwillingness. It is also called zealous energy (ātāpaviriya). It is an effort that has the four characteristics spoken of in the following text:–

“Kāmaṃ taco ca nahāru ca aṭṭhi ca avasissatu, sarīre upasussatu maṃsalohitaṃ; yaṃ taṃ purisathāmena purisaviriyena purisaparakkamena pattabbaṃ, na taṃ apapuṇitvā viriyassa saṇṭhānaṃ bhavissati.”

“Let only my skin, and sinews, and bones remain and let my flesh and blood in the body dry up, I shall not permit the course of my effort to stop until I win that which may be won by human ability, human effort and human exertion.” (Ai.50)

These characteristics may be summed up as follows:

- Let the skin remain,

- Let the sinews remain,

- Let the bones remain,

- Let the flesh and blood dry up.

It is the effort that calls forth the determination, “If the end is attainable by human effort, I shall not rest or relax until it is attained, until the end is grasped and reached.” It is the effort of the kind put forth by the Venerable Soṇa⁵⁰ and the Venerable Cakkhupāla.⁵¹

It is only when absorption, the paths, and fruits are not attained after effort is put forth on this scale, as prescribed by the Buddha and throughout one’s life, that it can it be said that the cause of failure lies in the nature of the present times, or in one being reborn with only two wholesome roots (dvihetuka), or in one’s lack of sufficient previously accumulated perfections.

In this world, some individuals, far from putting forth the full scale of effort prescribed by the Buddha, do not even try to set up body contemplation effectively in order to cure their minds of aimless drifting, and yet they say that their failure to attain the paths and the fruits is due to the fact that these are times that preclude such attainment. There are others of the same class who say that men and women of the present day do not have the necessary accumulation of perfections to attain the paths and fruits. There are yet others of the same class who say that men and women of the present day are reborn with only two wholesome roots. All these people say so because they do not know that these are times of teachable individuals (neyya) who fail to attain the paths and the fruits because they are lacking in strenuous right effort.

If proper effort be put forth with a firm resolution (pahitatta) where a thousand put forth effort, three, four, or five hundred of them can attain the supreme achievement; if a hundred put forth effort, thirty, forty, or fifty of them can attain the supreme achievement. Here, a firm resolution, means the determination to adhere to the effort throughout one’s life and to die, if need be, while still making the effort.

The Venerable Soṇa Thera’s effort consisted of keeping awake throughout the three months of the rainy season, the only body postures adopted being sitting and walking. The Venerable Cakkhupāla’s effort was of the same order. The Venerable Phussadeva Thera⁵² achieved the paths and the fruits only after twenty-five years of the same order of effort. In the case of the Venerable Mahāsiva Thera⁵³ the effort lasted thirty years.

At the present day, there is a great need for such kind of strenuous effort. It happens that those who put forth the effort do not have sufficient foundations in learning (pariyatti), while those who possess sufficient learning live involved in obstacles (palibodha) of the business of bhikkhus; according as they live in towns and villages these include such matters as discussing the Dhamma, delivering sermons and discourses, and writing books on the Dhamma. They are persons who are unable to put forth strenuous effort for lengthy periods without a break.

Some persons are inclined to say that when their perfections become ripe for them to attain release from worldly ills they can easily obtain that release and that, as such, they cannot put forth effort now when they are not certain whether or not that effort will result in release. They do not appear to compare the suffering occasioned by thirty years’ effort now with the suffering they will encounter if, in the interim before they attain release, they are cast in the hell regions for a hundred thousand years. They do not appear to remember that the suffering occasioned by thirty years’ effort is not as bad as the suffering caused by just three hours in the hell regions.

They may say that the situation will be the same if no release is attained after thirty years’ effort, i.e., they will be no closer to release. However, if a person is sufficiently mature for release, they will attain that release through that effort. If they are not sufficiently mature, they will attain release in the next life. Even if they fail to attain release within the present Buddha’s dispensation, the habitual kamma of repeated efforts at mental development (bhāvanā āciṇṇa kamma) is a powerful kamma. Through it one can avoid the lower realms, and can meet the next Buddha after continuous rebirths in the happy course of existence (sugati). In the case of those who do not put forth the effort, they will miss the opportunity of release even though they are mature enough to obtain release through thirty years’ effort. For lack of effort they have nothing to gain and everything to lose. Let all, therefore, acquire the eye of wisdom, and beware of the danger of not making effort.

There are four kinds⁵⁴ of right effort:–

- The effort to overcome or reject evil unwholesome states that have arisen, or are in the course of arising (uppannānaṃ akusalānaṃ dhammānaṃ pahānāya vāyāmo),

- The effort to avoid (not only in this life, but also in the lives that follow) the arising of unwholesome states that have not yet arisen (anuppannānaṃ akusalānaṃ dhammānaṃ anuppādāya vāyāmo,

- The effort to arouse the arising of wholesome states that have not yet arisen (anuppannānaṃ kusalānaṃ dhammānaṃ uppādāya vāyāmo),

- The effort to increase and to perpetuate the wholesome states that have arisen or are in the course of arising (uppannānaṃ kusalānaṃ dhammānaṃ bhiyyobhāvāya vāyāmo).

Arisen and Unarisen Unwholesome States

In the personality of every being wandering in saṃsāra, there are two kinds of unwholesome volitional actions, namely: arisen and unarisen.

The arisen unwholesome states means past and present unwholesome kammas. They comprise unwholesome volitional actions committed in the interminable series of past world-cycles and past lives. Among these there are some that have expired, having already produced rebirths in the four lower realms. There are others that await the opportunity of producing rebirths in the lower realms, which accompany living beings from world-cycle to world-cycle and from life to life.

Every being in whom personality-view (sakkāya-diṭṭhi) resides, be he a human being, a deva, or a brahma, possesses an infinitely large store of such past debts, so to say, consisting of unwholesome kamma that has the potential of producing rebirths in the lowest Avīci hell. Similarly, there is an infinite store of other kamma capable of producing rebirths in the other lower realms. These past kamma that awaits a favourable opportunity for producing rebirth resultants and which accompany beings from life to life until they are expended, are called arisen (uppanna).

These past arisen unwholesome kammas have their roots in personality-view. As long as personality-view exists, they are not expended without producing resultants. However, when one rids oneself of personality-view by gaining insight into the characteristic of not-self (anatta-lakkhaṇa), from that instant all the arisen unwholesome kammas lose their potential and disappear from the store of past unwholesome kamma. From that existence, one will no longer be subject to rebirth in the lower realms in future saṃsāra not even in one’s dreams.

Unarisen unwholesome kamma means future unwholesome volitional actions. Beginning with the next instant in this life, all the new evil and unwholesome acts that one commits whenever opportunity occurs in the course of this present life and in the succession of lives that are to follow, are called unarisen (anuppanna). The new unwholesome misdeeds that one can commit even during a single lifetime can be unlimited in number.

All these unarisen kammas have their origin in personality-view. If at any time personality-view disappears, all the new unarisen unwholesome kammas also disappear, even at that instant, from the personality of the beings concerned, leaving no residue. Here, “disappear” means that there will be no occasion, starting from the next instant, in the future succession of lives and the future succession of world-cycles, when new unwholesome kammas are perpetrated. Throughout future saṃsāra, those beings will not commit, even in their dreams, any unwholesome kamma such as killing living beings (pāṇātipāta).

If personality-view remains, even though he may be a Universal Monarch exercising sway over the whole world, he is, as it were, sandwiched between hell-fires in front and hell-fires behind, and is thus hedged in between the two types of arisen and unarisen unwholesome kammas. He is thus purely a creature of hell-fire. Similarly, the kings of the celestial realms, Sakka the king of Tāvatiṃsa, the Brahmas of the realms of form (rūpa-loka) and formless realms (arūpa-loka) are all purely creatures of hell-fire. They are creatures that are hitched on to the chains of hell and the lower realms. In the great whirlpool of saṃsāra, they are purely creatures who drift or sink.