Bhikkhu Pesala

The War on Error

Download a » PDF file (1.11 MB) to print your own booklets.

Order a Paperback Copy from Motilal Benarsidass.

Contents

Contents

The Preservation of the Religion

Foreword

When teaching at my own centre or in other Theravāda Buddhist centres I usually find that those who attend such classes and talks already have an interest in Theravāda teachings. However, when discussing Dhamma on Internet forums I come across the full spectrum of Buddhist thought from all schools of Buddhism. The teachings of the Buddha have spread to many different cultures over the centuries and have, in some cases, changed beyond all recognition.

Unlike many Buddhists of Southeast Asia, Western Buddhists have often come into contact with several of these divergent schools of thought, and many have also introduced their own ideas from western psychology or philosophy to further dilute or pollute the original teachings of the Buddha.

In the Mahāparinibbāna Sutta, the Buddha advised us to compare any teachings with the Dhamma and Vinaya, and to reject them if they do not fit with, but contradict the original teachings. We should be wary of accepting any teachings at face value. Those teachings that we have accepted should be re-examined constantly in the light of whatever knowledge we gain later.

All of us start from a point of not knowing, not understanding, and imperfect views. That is the nature of the human condition. If we were not deluded, we would not have taken rebirth in this world. The basic assumption for a Buddhist is that the Buddha knew something that we do not. To be a Buddhist, therefore, means that one must follow “The Way of Analysis,” or “The Way of Inquiry (Vibhajjavāda).” The Buddha’s teaching is not a religion, or a belief system, but a way of life and a practical method to develop the mind so that we can remove our ignorance, clarify our understanding, and gain right-view. The Pāḷi term for right-view — sammā-diṭṭhi — has a broader meaning than simply “right” as opposed to “wrong.” A Sammāsambuddha is a “Fully Awakened Buddha” so “sammā-diṭṭhi” means a view that is perfectly correct, fully in accordance with reality. While we are in the process of studying and practising the Buddha’s teaching, our view is gradually straightened out and refined to remove any imperfections until, on attaining the Noble Path and realising nibbāna, it becomes the perfectly correct view that is fully in accordance with the way things are.

The most reliable source we have for the Buddha’s teachings are the Pāḷi texts. Translations are not the original teachings, but interpretations by those who have some knowledge of Pāḷi. Some translations are more trustworthy than others, but if we really want to know what the Buddha taught then we have to go beyond intellectual knowledge, and practise his teachings to gain direct knowledge.

Nevertheless, before we can practise properly we do need to know what the Buddha taught, so there is much to be done by way of study, discussion, and systematic reflection. The Maṅgala Sutta lists thirty-eight auspicious signs of a prosperous future for one who fulfils them. Included in these thirty-eight are: 1) Not to associate with fools (asevanā ca bālānaṃ), 2) To associate with the wise (paṇḍitānañca sevanā), 7) Great learning (bāhusaccañca), and 8) Skill in work (sippañca), 26) Hearing the Dhamma at the right time (kālena dhammasavanaṃ), and 30) Discussion of the Dhamma at the right time (kālena dhammasākacchā), all of which are about acquiring knowledge.

The empty-headed are just a bit too quick to quote the case of “Empty-headed” Poṭṭhila, who was very learned in the scriptures, but still unenlightened. This elder quickly realised the Dhamma when he practised properly. I wonder how many of those who criticise academic learning have practised meditation seriously and gained insight?

Study, practice, then realisation is the natural order of things. In exceptional cases, when an intelligent, virtuous, and wise person meets an enlightened teacher, they may gain realisation with little or no study.

References are to editions of the Pāḷi Texts in Roman Script published by the Pali Text Society. In the PTS translations, these page numbers are given in the page headers or in square brackets in the body of the text. This practice is also followed by Bhikkhu Bodhi’s modern translations, like that below:

128 Sallekha Sutta: Sutta 8 i.44

Thus, a reference to M.i.44 would be found on page 44 of volume one in the Pāḷi edition, but on page 128 of Bhikkhu Bodhi’s translation. It would be on a different page in Miss I.B. Horner’s translation, but since the Pāḷi page reference is given, it can still be found. In the Chaṭṭha Saṅgāyana edition of the Pāḷi texts on CD, the references to the pages of the PTS Roman Script edition are shown at the bottom of the screen, and can be located by searching.

I have attempted to standardise the translation of Pāḷi terms, but it is impossible to be totally consistent as the various translations and editions are from many different sources. In the index you can find the Pāḷi terms in brackets after the translations.

The War on Error

The War on Error

Introduction

There are two opposing ways that one can look at the world: the religious view-point, and the political view-point. The political view-point is concerned with the external world, the behaviour of human beings and how their behaviour affects others in society. Politicians try to persuade and coerce others to behave as they wish, for what they perceive as the benefit of society and therefore of themselves. The religious view-point is concerned with the personal world, the behaviour of oneself, and how one’s own behaviour affects others in society. Religious people try to behave in a way that they perceive is of benefit to themselves and therefore to society.

In the following pages I will give a Buddhist’s view-point — not, please note, the Buddhist view-point, but my own view-point on how to wage the war on error and fight the real enemies of Buddhism. I will support my views with references to the Pāḷi texts, and I hope that you will read the available translations for yourselves to improve your own understanding of what the Buddha taught. If we regard ourselves as followers of the Buddha, then we should try to follow what he taught, not what others say that he taught, or what we think he should have taught. In other words, we should not just follow our own views and opinions, or even the views and opinions of learned monks, but we should make a thorough inquiry into the teachings of the Buddha, and then try to apply those teachings in our daily lives.

If we don’t make a thorough inquiry, then we are not waging war on error, but waging war in error. It won’t be a holy war, but a wholly inappropriate war for Buddhists to wage, and it will be a tragic waste of this very rare and precious human rebirth during an era when the Buddha’s teachings are still to be found in the world, and when there are still Noble Ones who know the right path leading to the end of all suffering.

Holy War in Buddhism

Holy War in Buddhism

Like other religions, Buddhism also has a concept of holy war. Ignorant people use such ideas to justify physical violence, intimidation, denial of basic human rights, and the oppression of others. However, there is only one holy war that deserves the name, and that is the struggle to be waged by each individual to remove his or her own craving and ignorance. No other war, crusade, or campaign is worthy of the appellation “holy.” Such battles with the external world do not lead to mental peace or to the cessation of defilements (nibbāna), but only to more suffering and greater ignorance. If you impose your views on others and deny them the right to hold different views, then you are not practising the Buddha’s teaching. Right-views can be promoted by teaching Dhamma, by pointing out what is not Dhamma, and by allowing others the freedom to decide for themselves which is which. If they choose the wrong path, that is for their loss and harm, but it is not your responsibility. Even the Buddhas can only show the way, those who claim to be his disciples must follow his instructions to reach the goal.

When the Dhamma is not properly practised, then the ignorant need to wage war in the name of protecting the religion, but actually all they are doing is protecting their own self-interest. This is not the way to preserve the Dhamma, but the way to destroy it. During wars, even if the nation is victorious, many lives are lost, much wealth is dissipated, many enemies are made, and the young men who return from war do so with both physical and mental scars. The way of the ideal Buddhist ruler — the Cakkavatti, or Wheel-turning monarch — is to conquer by means of generosity, friendliness, and by speaking the truth, not by the force of arms and threats of violence. Such a campaign, of course, would not be a war, but a diplomatic mission.

In the Milindapañha, King Milinda asked Venerable Nāgasena,

“Venerable sir, will you discuss with me again?”

“If your majesty will discuss as a scholar, yes; but if you will discuss as a king, no.”

“How is it then that scholars discuss?”

“When scholars discuss there is a summing up and an unravelling; one or other is shown to be in error. He admits his mistake, yet he does not become angry.”

“Then how is it that kings discuss?”

“When a king discusses a matter and advances a point of view, if anyone differs from him on that point he is apt to punish him.”

“Very well then, it is as a scholar that I will discuss. Let your reverence talk without fear.”

To preserve the Dhamma, we should discuss like scholars, not like kings. If we are unable to win over others to our point of view, then the fault lies not with the Dhamma, but most probably with our exposition of it. Even the Buddha himself could not win over everyone to be his disciple, so what can his ordinary disciples do? Finally, after all kindness, generosity, and reasoning have failed, we must practise tolerance, and abide in equanimity. The Dhamma will not disappear because non-Buddhists attack it and try to convert Buddhists to their faith, the Dhamma will disappear only when Buddhists fail to practise it properly.

Self-Defence

Self-Defence

What should Buddhists do when they are abused or attacked? How should they deal with aggression? A lady once asked me how she should deal with anger, so I advised her to contemplate the anger and the thoughts that gave rise to the anger, using the Satipaṭṭhāna method. However, I later learnt that what she meant to ask was, “How should I deal with aggression?” That is a different question entirely. It seems that her husband was in the habit of venting his anger on her. In this case, just being mindful with bare awareness of shouting or abusing is unlikely to be very effective. It might even make him more angry as he feels that he is being ignored and not getting the attention that he seeks. In this case, one should practise loving-kindness. Someone who regularly cultivates the practice of loving-kindness has very little fear or anger. They are no threat to anyone, so they rarely attract aggression. If one can develop deep insight into the human condition, then one can realise that there is nothing to defend. If there is no egoism, no self-interest, no craving, no expectations, no anxiety, how could anger arise?

However, most of us are not free from defilements yet, so how should we deal with abuse? Should we be a doormat or a punch-bag for others to use as they wish? I don’t think that this is the Buddha’s teaching. In Dhammapada verse 223 it says:

“Conquer anger by love. Conquer evil by good.

Conquer the stingy by giving. Conquer the liar by truth.”

When others tell lies about us, steal from us, or abuse us, we should defend ourselves. However, if we become angry, then that is a weakness in us from which we should learn. We should be long-sighted, not short-sighted. All beings are the owners of their kamma, and will inherit its results. The suffering that we are inheriting while being mistreated or abused is a result, but not all things are due to previous kamma. We can and should act in the present moment to deflect the fruition of past kamma as best we can. When we return anger with loving-kindness, stinginess with generosity, and speak the truth to expose lies, we are practising equanimity in the right way. If we do nothing, we are practising the equanimity of the water buffalo.

At one time, the Venerable Ajahn Chah asked a monk why he had not fixed the hole in the roof of his hut, from which water was coming inside. The monk replied that he was practising equanimity. Ajahn Chah said that that was the equanimity of the water buffalo.

If we practise that kind of equanimity, we may be strong, but we are behaving like a water buffalo. A human being should use wisdom to deal with problems that have arisen, using force if necessary, but not with anger. At one time, a shameless bhikkhu I lived with was constantly harassing me in various ways. After I returned from almsround one day, having walked six miles, he accosted me as soon as I returned, complaining that his telephone was not working. I immediately looked at his phone, and tested my own phone, to see if I could find an obvious fault. I could not, so I told him that I did not know why it was not working, and returned to my room to get ready for a shower, and to wash my almsbowl. The monk followed me into my room with his phone, still complaining that it was not working. So I made as if to follow him back to his room, and as he left my room I guided him out, and shut and locked the door to prevent him harassing me any further. For this I was accused by the Secretary of the Trust that supported the vihāra of “Committing an act of violence.” That is how corrupt people behave. They do not make a proper inquiry into the circumstances, but follow their own prejudices. If one can afford to, then one can also take legal action to defend one’s reputation — that option is not available to monks or most lay people due to the very high legal costs involved. One just has to put such injustices down to the fruition of past unwholesome kamma, let go, and move on.

When the circumstances demand it, Buddhists can and should use reasonable force to defend their own interests, but what is reasonable force is not written in any book. You have to decide that for yourself as circumstances unfold.

If we become angry — and there are plenty of things in this world that could make us angry if we are not mindful — then we will not be able to see clearly our own benefit, the benefit of others, nor the benefit of both. The Buddha gave the Simile of the Saw ¹ to advise us how to respond to violence.

“Monks, even if bandits were to cruelly sever your limbs with a two-handled saw, he who got angry even at that would not be following my teaching. Thus you should train yourselves: ‘My mind will not be corrupted and I will utter no evil speech. I will remain with compassion for their welfare, with a noble mind full of boundless loving-kindness, and free from hatred. I will abide pervading these individuals with a mind imbued with loving-kindness, I will radiate boundless loving-kindness to the entire world.’ That is how you should train yourselves.”

Of course, we understand that very few people are entirely free from anger — only Non-returners and Arahants have eradicated anger completely — but the Buddha’s advice is clear, if we follow his teachings properly we should conquer anger and violence by practising loving-kindness and patience, without limit. There is no justification in the Buddha’s teachings for waging war with weapons and bombs to kill other living beings. If, due to lack of mindfulness, patience, and compassion, we do resort to violence or warfare, that is a fault in us, and we will make unwholesome kamma if we harm others for our own short-term benefit.

However, do not misunderstand this teaching. We do not need to run away from aggression, but we should face up to it with courage and quiet determination. We can find examples in the texts of how the Buddha dealt with aggression, abuse, and threats to his life.

On one occasion, King Viṭaṭūbha, the son of King Pasenadi of Kosala, wished to attack and destroy the Sākyan race, and set off with his army. Knowing of the king’s intentions, the Buddha went to the road that he knew the army would follow and sat in the open near to a shady tree. When the king came there, the sun was getting high in the sky, and seeing the Buddha sitting in the hot sun, when there was a shady tree nearby, the king was surprised. He approach the Buddha, paid homage, and asked him why he wasn’t sitting in the shade. The Buddha replied, “While my relatives are alive, they provide me with protection and comfort, like that shady tree.” The king understood the Buddha’s meaning, and turned back his army.

What a noble example! How would we react if we knew that someone was planning to attack and kill our own relatives? Could we find some diplomatic approach like that to avoid bloodshed?

It is barely possible for ordinary people to respond in such a skilful way. We need to overcome our anger before we can see clearly enough to find the right way to deal with aggression — a way that is beneficial for both disputing parties. The first factor of the Noble Eightfold Path is right-view. To see clearly what is for our own benefit, for the benefit of others, and for the benefit of both, we need to establish right-view.

Remorse and Forgiveness

Remorse and Forgiveness

August 15th 2015 was the 70th Anniversary of Victory over Japan, commonly referred to as VJ-day. There was much discussion on a Buddhist forum that I visit whether the current US President should apologize to the Japanese for the dropping of the atomic bombs that led to the surrender of the Japanese seventy years ago. At the same time, there were several items in the media asking for the Japanese to apologize to the Korean “comfort women” who were abused by the Japanese soldiers during the war.

Some people think that such apologies are necessary to bring about reconciliation. My personal view is that such apologies are meaningless, and do nothing to address the divisions among generations far removed from the terrible events of that era. Even my generation, which is the one from shortly after the end of World War II, had no involvement in those events, and whatever we have learnt about them is coloured by the way that history was written about those events — mostly by the victors. We could not possibly understand how those personally involved feared for their lives at the time, and did manifold evil deeds misguided by propaganda and coerced by powerful leaders who had control over them.

Those younger than us, who are the descendants of that post-war generation, will feel even less responsible for the events of World War II. It is vital to study history to learn from former mistakes, but there is nothing that an apology can do to compensate the victims who suffered during that time. There might be a valid case for exchanging Japanese Military Yen for modern currency, or returning stolen works of art to their rightful owners, but what does a public apology achieve?

Those old people who suffered directly can benefit from studying the Buddha’s teaching on how to let go of the past, while living in the present, mindful that whatever we do in the present has consequences for the future. Dwelling with a mind overwhelmed by sorrow or ill-will has no benefit. If one receives no apology for the wrongs perpetrated by others, do not let it ruin your own happiness. Being a victim of a crime is a result of past kamma, which is called vipāka in Pāḷi, and there is nothing that anyone can do to prevent kamma from bearing fruit if its time is ripe. Even the Buddha had to suffer due to the fruition of past unwholesome kamma on several occasions during his lifetime, and the Buddha was unable to prevent the murder of his own Chief Disciple, Mahā-moggallāna, when his past evil kamma of murdering his parents in a previous life had to give its fatal results.

Remorse and Right-View

Remorse and Right-View

It is very likely that imperfect human beings will sometimes do unwholesome deeds due to the force of circumstances. Even in times of peace, good people are sometimes overwhelmed by lust, anger, or jealousy. A story from the Dhammapada Commentary will serve to illustrate the importance of remorse regarding doing evil deeds.

A couple were shipwrecked on an island of birds and survived into their old age by eating eggs and chicks. However, they felt not the slightest tinge of remorse about killing the chicks and eating the eggs. In the time of the Buddha, the man was reborn as Prince Bodhi, and his wife of that time again became his wife in that existence. Although they had been married for several years, they had no children, and wishing for blessings, they invited the Buddha and the Saṅgha for a meal. Their belief was that if holy men stepped on white cloths in their house they would get a child, so Prince Bodhi had the floors of the palace covered with white cloths.

When the Buddha arrived at the door of the palace, he did not enter even when invited three times by the prince. Venerable Ānanda looked at the Buddha, and guessing the reason, he told Prince Bodhi to have the white cloths removed. After the meal, the Buddha told the prince and his wife about the events of their previous life together, and explained that if they had felt remorse for their actions at any period during their previous life, they would not have remained childless in the current existence. However, as they had never felt any remorse at all they were destined to remain childless.

There are several lessons to learn about kamma from this story. Firstly, the law of kamma is not fatalism. Once a deed has been done, it is going to give a result, but its effects can be mitigated. A cricket ball may be dodged or deflected with a bat, a bullet may be stopped by a bullet-proof vest, but a missile is difficult to intercept even with another missile. If a large meteorite is heading our way there is nothing that can be done to prevent its impact, but one can still get out of its way if one knows that it is coming. Secondly, if an evil deed is repeated again and again, without any inhibition or remorse, its power accumulates. Thirdly, if one’s view is wrong, and one sees nothing wrong with doing evil deeds, the consequences are more serious. This may seem counter-intuitive, but it is true, and ignorance is no defence. The example given in the Debate of King Milinda is of getting burned more severely if one picks up a red-hot iron ball without knowing it is hot, as opposed to picking it up knowingly.

If we ever do evil deeds we should acknowledge them, at the very least to ourselves if not to the victim or to a spiritual preceptor. The Buddha said that it rains hard on what is covered, it does not rain hard on what is open. There is a ceremony that the monks perform at the end of the Rains Retreat, called the Invitation Ceremony (Pavāraṇā), where the monks invite others to admonish them if they have seen, heard, or suspected them of committing any offence against the Vinaya rules that has not been disclosed.

Asking for Forgiveness

Asking for Forgiveness

There is no need to apologize for the evil deeds done by others, but if one has personally done harm to others it is very helpful to ask them for forgiveness. This benefits both parties. If the injured party is willing to forgive the offence or harm caused, the parties can be reconciled and become friends again. If not, at least it will lighten the burden of remorse and guilt for the one who did wrong.

The wicked monk Devadatta did many evil deeds during his life time, but during the final moments of his life he had sincere remorse and took refuge in the Buddha. The Buddha predicted that in the distant future, after suffering in hell for aeons, he will become a Solitary Buddha. Prince Ajātasattu, who conspired with Devadatta, and killed his own father, was greatly remorseful regarding his own evil deeds. His evil kamma would inevitably bear fruit after his death, but after he acknowledged his fault to the Buddha, he was able to sleep peacefully again. According to the Commentaries he will also become a Solitary Buddha in the distant future.

Wrong-Views

Wrong-Views

To understand right-view, we need to know about wrong-views. There are many kinds of wrong-view. All are harmful, but some are more dangerous than others. Later I will discuss the heretical views that are especially dangerous, but I will begin with two wrong-views that are almost universal in the world — eternalism and annihilationism.

Eternalism (sassata-diṭṭhi)

Eternalism (sassata-diṭṭhi)

1. The first wrong-view is that the self is indestructible, that it exists forever. This is eternalism. Its adherents hold that although the physical body is destroyed at death, the soul or self passes on to another body and continues to exist there. Those who are firmly attached to this belief cannot hope for spiritual progress. This wrong-view is a major impediment to the realisation of nibbāna. Although it is not clung to firmly by well-informed Buddhists, one cannot remove it completely until one realises nibbāna and becomes a Stream-winner.

Annihilationism (uccheda-diṭṭhi)

Annihilationism (uccheda-diṭṭhi)

2. Opposed to eternalism is annihilationism. According to this belief, the ego-entity only exists until the dissolution of the body, after which it is annihilated. These days this belief is very common because materialists reject the idea of a future life on the grounds that it cannot be proved scientifically. Annihilationism has become popular because of the rejection of traditional beliefs, distrust of religious leaders, and due to a strong desire to enjoy sensual pleasures in the present life. Buddhists are also atheists, i.e. they do not believe in an Almighty God or Creator. However, they are not annihilationists because they do believe in kamma and rebirth. According to the Buddha’s teaching, mind is the forerunner, mind is the chief, and all things are mind-made.²

There is neither an immortal soul, nor annihilation after death. Buddhism denies the existence of any permanent ego-entity, but it recognises that the psychophysical process is conditioned by the law of cause and effect. There is continuity of a process, not of a person or being. Causes such as ignorance give rise to effects such as mental-formations (saṅkhārā). Mental formations in turn give rise to consciousness, and so forth. Death means the final dissolution of the psychophysical organism, which is subject to disintegration. However, death is not annihilation. Due to defilements, and conditioned by kamma, physical and mental events take place in unbroken succession as before, in a new rebirth into any of the six realms of existence.

Rebirth is neither the transmigration of a soul nor the transfer of mind and matter from one life to another. The physical and mental phenomena arise continually and always pass away. Death destroys all mind and matter completely, but new psychophysical phenomena of existence arise in a new life, and these are causally related to those in the previous life. The rebirth-consciousness and other psychophysical factors arise as a result of the attachment to any vision or sign (nimitta) relating to one’s kamma or future life at the moment of one’s death.

Since there is no self, it is a mistake to believe in an immortal soul that survives death, but it is equally wrong to speak of annihilation. The psychophysical process will continue as long as it is not free from defilements.

Self-view (sakkāya-diṭṭhi)

Self-view (sakkāya-diṭṭhi)

3. A third wrong-view, which is almost universal even among Buddhists, is the belief in a self or soul. Buddhists have been taught that the so-called self is illusory, but unless they have practised insight meditation to a considerable extent, the belief will persist. It is not entirely removed until the meditator realises nibbāna and becomes a Stream-winner, but a diligent meditator can gain insight into the Buddha’s teaching through direct personal experience. It is similar to the case of those who know how magic tricks are performed. If one does not know how illusionists perform their art, their tricks are extremely convincing. If one knows the secret, then one is not deceived, but the illusion is still very effective.

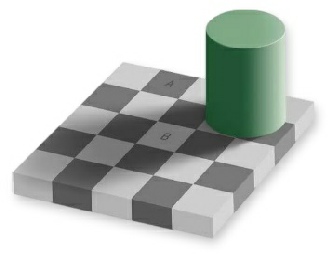

Look at this optical illusion. The two squares marked as A and B are the same shade of grey. Though I have told you this, you may not believe me. The illusion is extremely convincing, and some people are not easily persuaded that the two squares are identical shades of grey. However, an intelligent person or someone who had faith that Buddhist monks do not usually tell lies, will make a proper investigation of the image to see if what I say is true or not. If you have done that investigation, you will know without any doubt that what I say is true since both squares have a RGB value of 120,120,120. However, the illusion remains just as convincing as before. The mind is completely deceived by the shadows and contrast.

Look at this optical illusion. The two squares marked as A and B are the same shade of grey. Though I have told you this, you may not believe me. The illusion is extremely convincing, and some people are not easily persuaded that the two squares are identical shades of grey. However, an intelligent person or someone who had faith that Buddhist monks do not usually tell lies, will make a proper investigation of the image to see if what I say is true or not. If you have done that investigation, you will know without any doubt that what I say is true since both squares have a RGB value of 120,120,120. However, the illusion remains just as convincing as before. The mind is completely deceived by the shadows and contrast.

It is similar with self-view. The illusion is deeply rooted at the level of perception, so no amount of reading of Buddhist literature or listening to Dhamma talks will make much difference. We may be fully convinced on the intellectual level that the Buddha was Fully Enlightened and that his teaching is flawless, but that does not eradicate self-view. There is only one way to remove this serious error, and that is through practising insight meditation — seriously and intensively, not casually or occasionally.

The mind is exceedingly rapid. Without practising meditation seriously it won’t be possible for the average person to see through the illusion of self. Egoism is too deeply rooted and the belief in a self or person, “I” or “You,” is too convincing. The average person identifies strongly with his or her nationality or racial group. National pride, racial prejudice, and narrow-mindedness have a fertile breeding ground as long as this very serious error of self-view is not dissolved through the practice of insight meditation. It is a dangerous error because it takes the impermanent to be permanent, the unsatisfactory to be satisfactory, and that which is devoid of self to be a self. Anyone still holding this view will expend most of their energy in the pursuit of sensual pleasures. A monk may not pursue coarse sensual pleasures such as sex, music, or food, but he will still be striving to satisfy the ego by seeking praise and status. If he is lacking in basic morality, then he will seek material gain such as money, property, and other things that are unsuitable for one who claims to be a renunciate.

Among Buddhists as well as non-Buddhists, there are many degrees of ignorance regarding this so-called self. Even among well-informed Buddhists who have studied the Buddha’s teachings in depth, the illusion may persist and remain strong due to lack of insight into the workings of the mental and physical process. An uneducated person who has practised insight meditation effectively will have a better understanding than a learned person who has not practised meditation, because insight arises from direct experience of reality, not from conceptual thought.

Non-dhamma (adhamma)

Non-dhamma (adhamma)

It is now over 2,500 years since the Buddha passed away, and his teaching has spread to many parts of the world. Over the centuries, due to contact with other religions, and the natural process of decay that is inherent in all conditioned things, many heretical views have infiltrated into the Buddhist religion. In the West, if we use the word ‘heresy’ it tends to conjure up pictures of people being tortured on racks and burnt at the stake, so it is better to call it non-dhamma (adhamma). Buddhists don’t torture heretics. They are compassionate, or at least they should be if they are sincere followers of the Buddha. The meaning of heresy is “any opinion or doctrine at variance with the official or orthodox position.”

If one says that the Buddha taught what he did not teach, or that he practised what he did not practise, then that is a heresy. Similarly, if one says that he did not teach what he did teach, or did not practise what he did practise, then that is also heresy. However, for the benefit of those over-sensitive people who are afraid of being burnt at the stake if we disagree with them, we will refer to heresy as “non-dhamma.”

If a person maintains, “The Śūraṅgama Sūtra is definitely the word of the Buddha,” he will be regarded as teaching non-dhamma by those who maintain, “The Śūraṅgama Sūtra is definitely not the word of the Buddha.” If someone says, “To be a compassionate Buddhist, you must be a vegetarian,” they will be regarded as teaching non-dhamma by someone who understands according to what the Buddha Kassapa said in the Āmagandha Sutta that purity and impurity do not come from what we put into our mouths, but from what comes out of our mouths.

“Taking life, beating, wounding, binding, stealing, lying, deceiving, worthless knowledge, adultery; this is stench. Not the eating of meat.” ³

Dhamma and non-dhamma are farther apart than the sky and the earth. It is vital that one studies the Dhamma carefully and rightly understands, “This is the teaching of the Buddha,” or “This is not the teaching of the Buddha.” If one firmly accepts non-dhamma as Dhamma, one will accumulate a great deal of unwholesome kamma defending that wrong-view, and criticising those who hold right-views.

For example, the Dalai Lama says, “Those Arahants who have conquered the disturbing emotions are in a temporary state. They have not attained a final state. Due to the remaining obscurations they regard body and speech as ‘mine.’ Even though they are no longer motivated by disturbing emotions, the cognitive obscuration, which is a sense of a self, an ‘I’ and ‘mine’ manifests in their physical and verbal activities. Their conquests and achievements for their own sake are temporary. They are not capable of benefiting others ultimately.”

This teaching — which originates from the Mahāyāna Sūtras — is non-dhamma. It is diametrically opposed to the teachings in the Tipiṭaka that the Arahants have reached the final goal, and done what should be done. It is also diametrically opposed to the teaching that says that all of the Noble Ones are worthy of offerings, worthy of gifts, worthy of reverential salutation, an incomparable field of merit for the world. That is, an offering to any Noble One, paying homage, or doing service for them is of immense benefit for the pious Buddhist who has faith in the teaching of the Buddha. Even the Stream-winner is completely free from self-view. Stream-winners do not regard body and speech as ‘mine.’ Their conquests and achievements are irreversible and final. They will not fall back again to a lower stage of being an ordinary ignorant worldling, wandering in saṃsāra indefinitely. Within seven rebirths at the most, they will realise the final cessation of suffering with the attainment of Arahantship.

What the Dalai Lama says is non-dhamma. It is very harmful to the interests of those who would make offerings or pay homage to Noble Ones. It is harmful to those who would make offerings or pay homage to stūpas that are built over the remains of Noble Ones, because the Buddha said that they are worthy of homage (arahaṃ). Even if one pays homage or makes offerings to an ordinary monk or nun who is still a worldling, because they are wearing the robes of the Noble Ones, and maintaining the traditions of the Noble Ones, then one makes a great deal of merit by thinking about the noble attributes of the Noble Ones, such as having few wishes, being easily supportable, modest, honest, and so forth. Therefore, saying that the Arahants are not capable of benefiting others ultimately is a serious wrong-view.

As the Buddha taught in the Abhāsita Sutta (What was not said):

“Monks, these two slander the Tathāgata. Which two? He who explains what was not said or spoken by the Tathāgata as said or spoken by the Tathāgata. And he who explains what was said or spoken by the Tathāgata as not said or spoken by the Tathāgata. These are two who slander the Tathāgata.” ⁴

Slandering ordinary, unenlightened beings by saying that they said what they did not say is unwholesome kamma. Slandering the Buddha is much more serious, and harmful to many people.

Pointing out non-dhamma as non-dhamma is not slander. It is not unwholesome kamma. Clarifying and distinguishing what is Dhamma and what is non-dhamma is the meritorious deed of teaching Dhamma. It is not a personal attack on the Dalai Lama. It is his teaching that is at fault, not the person. He is just repeating what he has been taught from a young age, without careful reflection as to whether it is really true or not. What you must decide for your own well-being and happiness is what is Dhamma and what is non-dhamma. Not who is right and who is wrong. Your decision must not be biased or prejudiced because you like one person or dislike another.

Are Arahants of any benefit to others or not? That is what you need to decide. If you could study the Dhamma with an Arahant, would that be beneficial to you or not? If you could pay homage or offer almsfood to a genuine living Arahant, would that be beneficial to you or not?

Those who are not Arahants teach Dhamma with a mind defiled by greed, hatred, and delusion. The Dhamma is still good, whoever teaches it, but won’t the teaching of an Arahant be really lucid and clear, powerful and memorable, due to the Arahant’s clear insight and perfect mental purity? Would listening to that pure Dhamma teaching be beneficial or not? Would it lead to life-long happiness and spiritual progress, or to life-long misery and spiritual decline?

Is it really true, as the Dalai Lama says, that “Arahants are not capable of benefiting others ultimately?” If it is false, should we criticise that teaching of the Dalai Lama or not? If it is false, does that mean that all of the Dalai Lama’s teaching is false, or only some of it? Is the Dalai Lama telling lies, or merely speaking falsehoods?

We should be fearless when deciding what is Dhamma and what is not; when saying what is Dhamma and what is not. If we are doubtful about what is Dhamma and what is not Dhamma, we should remove our doubts, shouldn’t we? That can be done by careful, systematic study, and through the practice of meditation. Study, practice, and realisation.

Defeating the Enemy

Defeating the Enemy

To remove the illusion of self-view is not at all easy. We have to fight the holy war to defeat the enemy, who is called Māra. Māra is an illusionist who deceives people and holds them under his control. Because they are controlled by Māra, or under the spell of illusion, most people do not consider it necessary or desirable to renounce sensual pleasures, and to spend many days, weeks, months, or years in meditation centres and monasteries. They wallow in the temporary and hollow satisfaction afforded by sensual pleasures, praise, status, and fame. If a monk or experienced meditator does persuade them to take up the practice of insight meditation, when the time comes for them to go to the meditation centre, Māra intervenes and persuades them not to go. Something else more important suddenly crops up. They get sick, they have to help their friend, they have to take the dog to the vet. Whether the excuse is obviously lame or apparently genuine, you can be sure that Māra will prevent them from practising meditation.

Others are a bit more determined. They do actually get to the meditation centre, but after a few hours or a few days, Māra comes along and urges them to give up. “Why do we have to practise so long. I need to take a break. The Buddha’s way is the Middle Way; striving hard like this is self-torture.” Unless the teacher can convince them to persist with their meditation practice, these people soon give up and go back home. If the teacher is successful, and they continue to strive hard to the best of their ability, Māra will not go away, but will continue to obstruct the meditator’s progress at every opportunity. It is this battle with the internal enemy that is the true holy war. To fight this holy war we need great courage, determination, and intelligence. However, unlike other so-called holy wars, this one does no harm to anyone — not even to oneself. The harder one fights to overcome Māra, the stronger one’s mind becomes. Even if one loses some battles, and Māra gains the upper-hand, the courageous meditator never gives up, and learns from his or her defeats to become a better holy warrior.

Five kinds of Māra

Five kinds of Māra

1. Māra Devaputta

This is the powerful deity who tried to obstruct the Bodhisatta on the night of his Enlightenment. He resides in the highest realm of the sensual plane, Paranimmitavasavatti devaloka, or the realm of those who delight in the creations of others. Those who, due to many meritorious deeds done in the past, are able to indulge in whatever sensual pleasures they like, who enjoy robust health, and have many friends and supporters, will find it very difficult to see the truth of suffering. They will be disinclined to listen to teachings about impermanence, suffering, and the renunciation of pleasure. Not only will they not incline towards such teachings, they will be strongly opposed to them. Māra devaputta is like any individual who has great power and influence — he does not want to see that influence undermined. In the human realm, political leaders, military dictators, or industrial oligarchs who hold great influence, power, or wealth, are vehemently opposed to anything that might weaken their position.

2. Kilesa Māra

2. Kilesa Māra

The mental defilements that arise to obstruct us whenever we try to do wholesome deeds such as giving charity, undertaking and observing morality, or cultivating meditation. If the eye is clouded by a cataract, if the air is filled with smoke, or if it is night and there is no light, we cannot see clearly. If the ear is full of wax, or distracted by extraneous noises, we cannot hear clearly what we wish to hear. Likewise, if the mind is clouded by mental defilements like lust, anger, conceit, bigotry, or dullness, we cannot understand clearly. To know things as they truly are requires mental purity and deep concentration.

3. Abhisaṅkhāra Māra

3. Abhisaṅkhāra Māra

These are volitional activities or mental formations (kamma). Although wholesome kamma gives agreeable results such as long life, good health, prosperity, and so forth, it prolongs the cycle of existence. The pleasant results of wholesome kamma help to conceal the truth of suffering, and habitual busy activity keeps the mind constantly restless and confused, such that it cannot always clearly distinguish what is wholesome from what is not. However, the wholesome deed of insight meditation does not prolong the cycle of existence, as its aim is to reveal the truth of suffering.

4. Khandha Māra

4. Khandha Māra

As long as we are reborn with the aggregates of existence, then suffering will continue. The body demands food and water, clothing and shelter, care and attention, and the mind demands new sensory contacts to keep it stimulated. As long as we are attached to the aggregates, we will be making fresh kamma.

5. Maccu Māra

5. Maccu Māra

Life is short, and there are many things to be done by one born into this human realm. When we are first born we do not even know how to eat, clean our own bodies, or walk. Then we have to learn how to speak, read, and write. After that, we have to learn many kinds of secular knowledge and skills just to survive. If all goes well, we may reach a mature age without mishap, and get a precious opportunity to hear the Buddha’s teaching. If we are wise enough to understand it, we may gain faith in it and want to practise to gain liberation from rebirth. However, finding time to practise meditation seriously is difficult.

Too many Buddhists get old and senile without so much as setting one foot on the practical path of mindfulness. All too often, death intervenes, rebirth inevitably follows, and the process begins all over again. If, as a result of unwholesome kamma, one is reborn in the lower realms, the precious opportunity to practise the Buddha’s teachings to gain liberation from suffering is lost. If, as a result of wholesome kamma, one is reborn in the human realm, one must again learn how to eat, walk, speak, read, and earn a living all over again. If, as a result of wholesome kamma, one is reborn in celestial realms, one may still be heedless and negligent regarding the real practice leading to nibbāna.

Death is finally overcome only when one becomes an Arahant. The Arahants are no longer afraid of death, having eradicated all attachment to the aggregates. They have done what ought to be done by one born human.

The meditator must fight the mental defilements, notably the five hindrances that obstruct the development of concentration. Sensual desire, ill-will, sloth, restlessness, and doubt are the five hindrances that prevent the development of concentration. Without deep concentration and mental purity it will be impossible to gain insight. Whenever any one of these five hindrances appears, the meditator should note it with mindfulness to dispel it. The five powers of confidence, effort, mindfulness, concentration, and wisdom are the weapons with which to defeat the defilements. The pure-hearted meditator who is always inclined towards nibbāna will conquer the other kinds of Māra too.

The Armies of Māra

The Armies of Māra

Sensual Pleasure

To take up the practice of meditation in earnest, one must first renounce indulgence in sensual pleasures. Although it is not necessary to become a monk or a nun, if one wishes to develop concentration it is essential to observe chastity and to avoid entertainments during the period of practice. It is impossible that anyone, even a monk or nun, could gain deep concentration and insight while still indulging in, longing for, and thinking about sensual pleasures of various kinds.

Discontent

Discontent

At first, meditation is difficult. When the mind that is accustomed to enjoying sensual pleasures is withdrawn from and no longer allowed to follow its usual habits, there will be a reaction. It is like taking a piece of red-hot iron from a fire, and plunging it into cold water. It won’t be quiet, but will react violently. However, as one develops concentration and mindfulness, the mind will gradually become cool, then there is no longer such a strong reaction. After some time, the meditator will begin to enjoy continuous meditation, and won’t want to indulge in sensual pleasures at all. It is like someone on a long journey, who is resting in the shade of a tree. He or she is reluctant to go out again into the hot sunshine. Or, it is like someone who has had a bath and put on clean clothes. He or she does not wish to work and get dirty and sweaty again.

“Old habits die hard” as the saying goes. If one has indulged in sensual pleasures excessively and for a long time, one will have to work very hard to overcome discontent. If one has lived a modest and scrupulous moral life for many years, it will not be so difficult.

Hunger and Thirst

Hunger and Thirst

Everyone needs to eat and drink, even a diligent meditator. However, we don’t need to eat three meals a day. A meditator should be content with two meals or just one. The Buddha recommended that one meal a day was the best for good health. Food should be taken with mindfulness, not indulging in the pleasure of tasting and eating, but reflecting wisely so that one eats just for the sake of nutrition.

Craving

Craving

Craving is the proximate cause of suffering, and it has many facets. Even when the meditator has overcome the stronger forms of craving for sensual pleasures, and craving for this or that kind of food, he or she may start longing for other things. He or she may hear about another meditation centre, or another teacher, or another style of meditation practice. The meditator may start getting attached to blissful states, or on hearing other meditators reporting their experiences in meditation to the teacher, he or she may start longing for similar experiences.

One should remember that the essence of meditation practice is to remain mindful of the reality in the present moment. Unusual experiences and insights will arise when the conditions are ripe, and not before. If you long to make good progress, then make good efforts. Longing for, thinking about, and wishing for special experiences does not lead to them; working hard to develop constant mindfulness and deep concentration does.

Sloth and Torpor

Sloth and Torpor

Everyone needs to sleep. Even diligent meditators need some sleep. Doctors recommend that one needs eight hours a day, but doctors don’t meditate diligently. Meditation teachers recommend that one sleeps six hours a day at the most, and that four hours is sufficient for a really diligent meditator. How much sleep a meditator needs will depend on how good their concentration is. Individuals have a wide range of abilities. A beginner may struggle to get by on only six hours sleep, while a meditator who has attained deep insights may need very little or no sleep at all for several days at certain stages on the Path. If you listen to Māra, he will always tell you that you need more sleep. A holy warrior should always be on the alert, and ready to get up and start fighting.

Fear

Fear

At the higher stages of insight, one will encounter unusual and unpleasant experiences. When entering unfamiliar territory, everyone feels apprehension and fear. The final goal of the practice is to overcome aging, disease, and death, and everyone is afraid of death. If one gets some disease, it may get worse or it may be cured by the body’s natural immunity after some time. One can call a doctor and take medicine, but not all diseases are cured by medicine. There is no medical treatment that can prevent one from getting old. Even though one may be very careful about diet, personal hygiene, and exercise, one will still get old, and have to face death eventually. In spite of all the precautions that one may take, one’s past kamma may bear fruit at any moment and cause death. A meditator should, therefore, confront fear whenever it arises and rely on their confidence in the Buddha, Dhamma, and Saṅgha to protect them from danger.

Doubt

Doubt

Buddhism is unique among religions in that it does not encourage belief. On the contrary, it encourages critical examination and analysis. A meditator should make a thorough investigation and test the theory to see if it works. During the time of the Buddha, a monk named Bhaddāli heard that the Buddha recommended eating only one meal a day. The other monks told him about it, but he liked to eat in the evening too. He reasoned, “I abide in comfort eating whenever I feel hungry, so why should I give up eating in the evening?” Although this was contrary to the training rule laid down for monks not to eat after midday or before dawn of the following day, Bhaddāli thought he knew better. He was overwhelmed by Māra. He doubted that the Buddha’s advice would help him to develop concentration and insight. For the entire Rains Retreat, he continued to follow his wrong practice, and the Buddha said nothing, but after the Rains, the Buddha admonished Bhaddāli and made him realise how attached and lazy he was.

Many meditators are like Bhaddāli. Although meditation teachers recommend that they practise continuously without a break for long periods, they are reluctant to do so. They think that an hour, or just half an hour, is long enough. Without doubt, meditating for one hour every day will be beneficial and will reduce stress in one’s life. However, it won’t be nearly enough to gain deep concentration and insight. I hold regular one-day meditation retreats from 7:00 am until 7:00 pm at my centre, but very few meditators come to practise. Yet, twelve hours is only half a day, not even a full day. Some want to practise for only six hours. Perhaps some lazy monks have taught them that prolonged, continuous, and strenuous practice is not following the Middle Way. Definitely they have been defeated by Māra. They are not holy warriors.

Conceit and Ingratitude

Conceit and Ingratitude

If a meditator overcomes the earlier armies of Māra, he or she may gain some results from their practice. He or she may be able to sit for long periods without moving, and may experience blissful mental states, lightness of the body, or other unusual experiences. In some cases, an inexperienced meditator with inadequate scriptural learning may think that enlightenment has already been reached, although it has not. Such meditators become forgetful of their dependence on their teacher. Although their teacher may have been meditating for thirty, forty, or fifty years and they have only practised for five or ten years, they may think that their experience is superior to anything that their teacher knows. Others, even non-meditators, can see that they are conceited, but they themselves cannot see it. They are completed blinded by the light of their own wisdom. Someone who has fallen into this serious error is very difficult to cure. It is one reason why an experienced meditation teacher should be relied upon for guidance. Even an unenlightened teacher with a sound knowledge of the texts is preferable to a teacher who is suffering from excessive conceit.

Gain, Praise, Honour, Undeserved Fame

Gain, Praise, Honour, Undeserved Fame

Some monks seek academic qualifications, as without them it is hard to be appointed as the abbot of a monastery. Others travel abroad to gain degrees at universities under the tutelage of lay Buddhists, rather than following the traditional monastic training in Dhamma and Vinaya. Such qualifications may be essential for lay people such as doctors and engineers, psychologists and lawyers, but this is the way of the world, not the way of Dhamma. When one follows the way of Dhamma, knowledge and wisdom are the essential qualifications — gain, praise, and fame are dangers to the spiritual life.

Learning the Dhamma in detail is obviously a good thing to do, but the motivation must also be right. The essential thing is to know what the Buddha taught, and then to apply that teaching in one’s own life. In teaching meditation and giving Dhamma talks, the speaker should be thinking of the welfare of the audience, otherwise the teaching is corrupted by desire for gain, praise, honour, and fame. What does it matter if only one person is listening, or a thousand?

The number of people in the audience is no measure of the wisdom of the speaker. In this world, the foolish far outnumber the wise. Twenty-eight million viewers used to watch Morecambe and Wise, but who among them was truly wise? Such comedians who entertain people may think that they are spreading joy and laughter, but that kind of happiness is worthless. In fact, it is worse than useless as it encourages stronger attachment and greater delusion.

When teaching the Dhamma, if one strives to be popular by telling stories and jokes, one may become famous, but at what cost? If desire for praise and fame is the motivation, then the purpose of Dhamma is lost and the teaching becomes corrupt. The suttas are not lacking in humour, but no comedy can be found there. Read some of the suttas such as the Payāsi Sutta, ⁵ and see if you can understand what I mean by the difference between humour and comedy. There, the Venerable Kumāra Kassapa teases Prince Payāsi, making fun of his attachment to his wrong-views. The purpose is to make him let go of those wrong-views, which will be for his benefit. If we use humour in the right way, it is a skilful means — but we shouldn’t misuse it. Māra’s army of wishing for praise and fame is hard to overcome.

Venerable Sāriputta was praised by the Buddha as the wisest of his disciples, as the one who was the most capable to teach the Dhamma after himself. When the Venerable Sāriputta heard good reports about the Venerable Puṇṇa Mantāṇiputta, he went to see him to have some conversation with him, travelling on foot in stages the long distance from Sāvatthi to Rājagaha. Their conversation is found in the Rathavinīta Sutta ⁶ — The Discourse on the Relay of Chariots. The two monks rejoiced in each others questions and answers. Later, the Buddha praised Puṇṇa Mantāṇiputta as the best expounder of the Dhamma among his disciples.

This is the nature of wise teachers. They recognise and praise the good in others, while being modest about their own knowledge and abilities. Inferior teachers think highly of their learning, jealously guard their disciples, and discourage them from practising with other teachers.

Self-praise and Disparaging Others

Self-praise and Disparaging Others

Someone who is not well-rooted in the practice will often resort to self-praise and the disparagement of others. It is due to lack of self-confidence. Actually, his or her practice may not be so bad, but due to his fault-finding nature it never seems to be good enough. It is only human to have faults and defects. If we openly admit them, then we can work to remove them. If we conceal our faults, and pay more attention to the faults of others, it will be difficult to make any further progress.

If we have acquired firm confidence in the teachings of the Buddha, and are sincerely striving to observe precepts, whether five, eight, ten, or 227 precepts, then we are heading in the right direction. The spiritual training is a gradual path, and a life-time job. Only those who strive with the utmost determination can reach the final goal in this very life. It is vital not to underestimate the task, but one also needs to rejoice in what has been accomplished already. If we have a realistic appraisal of our virtues as well as our vices, then we won’t feel the need to praise ourselves or disparage others.

If we wish to criticise, we should only criticise attachment, aversion, or wrong-views. Don’t blame the person, lay the blame squarely on the shoulders of mental defilements. Any person who has taken rebirth in this world still has mental defilements, unless they have eradicated them by developing the Noble Eightfold Path, until reaching the final goal of Arahantship. Unless we are Arahants, we all deserve to be criticised.

“This, Atula, is an old saying; it is not one of today only: They blame those who are silent, they blame those who speak too much. Those speaking little they also blame. No one avoids blame in this world. (Dhp v 227)”

Right-Views

Right-Views

Opposed to wrong-view is right-view (sammā-diṭṭhi), which is the first factor of the Noble Eightfold Path as taught in the Buddha’s First Discourse, the Dhammacakkappavattana Sutta. As with wrong-view, there are many grades of right-view. In brief, it means to see things as they truly are — to understand things in accordance with reality. Prior to attaining the first stage of the path and becoming a Stream-winner, this right-view is called mundane right-view. At the moment of attaining the path and realising nibbāna, when right-view becomes mature, it is known as supramundane right-view.

To acquire the mundane right-view one should study the Buddha’s teaching, question learned Buddhist monks and scholars regarding the meaning, and reflect on that teaching using one’s own native wisdom and intelligence to see if it accords with one’s own personal experience. This process of cultivating right-view is the wholesome deed of straightening one’s view (diṭṭhūjukamma). It is vital not to accept any teachings at face value, but to examine them carefully, as one would if invited to purchase gold or gems.

A misconception among some today is that only meditation practice is important when it comes to understanding the Buddha’s teaching, and that study is next to useless. The story of “Empty-headed Poṭṭhila” is often quoted in support of this view. This elder in the time of the Buddha was learned in the teachings and used to instruct five hundred bhikkhus. After receiving instruction from him, many of his students went to the forest, meditated, and gained Arahantship. The Elder Poṭṭhila, however, was too busy teaching to do much meditation himself, and so gained no special insight knowledge or attainments. When he met the Buddha, the Buddha referred to him as “Tuccho Poṭṭhila — Empty-headed Poṭṭhila.” The elder took the hint, learnt meditation from a young novice who was an Arahant, and gained Arahantship himself.

It is true that developing mindfulness and wisdom is the only way to gain realisation of the Dhamma, and to put an end to suffering. However, if we don’t have respect for learning we may practise wrongly, and instead of gaining nibbāna, we will go far astray from the right path. The pupils of Poṭṭhila who became Arahants first studied the Dhamma respectfully under him, and then practised meditation. Study should come first, then correct and systematic practice, which will lead to realisation only if done with sufficient diligence.

Satipaṭṭhāna — The Only Way

Satipaṭṭhāna — The Only Way

Correct and systematic practice refers to the development of mindfulness (satipaṭṭhāna) with the purpose of gaining insight (vipassanā). The Satipaṭṭhāna Sutta is the Buddha’s most important teaching on meditation. There are two versions of it: one in the Long Discourses ⁷ and one in the Middle Length Sayings.⁸ We should study this discourse in some detail if we wish to cultivate mindfulness and gain insight.

It should not be misunderstood that there is only one way to practise meditation — there are many different ways to cultivate mindfulness, and there are many other discourses on meditation. By “The Only Way” it means that the goal cannot be reached without right-mindfulness and the other seven factors of the Noble Eightfold Path.

The discourse was addressed to bhikkhus, but is suitable for all who aspire to gain insight and realise nibbāna. The Commentary says that the discourse was given among the Kuru people because even the servants and workers there were in the habit of practising mindfulness. Anyone who did not practise mindfulness was liable to be criticised for being negligent.

Introduction to the Discourse

Introduction to the Discourse

In the introduction to the Satipaṭṭhāna Sutta the Buddha said:

“Ekāyano ayaṃ, bhikkhave, maggo sattānaṃ visuddhiyā, sokaparidevānaṃ samatikkamāya, dukkhadomanassānaṃ atthaṅgamāya, ñāyassa adhigamāya, nibbānassa sacchikiriyāya, yadidaṃ cattāro satipaṭṭhānā.”

Ekāyano maggo: means that this is the only path, the most direct way, or the Noble Eightfold Path that culminates in the realisation of nibbāna (nibbānassa sacchikiriyāya), which is the cessation of suffering.

Sattānaṃ visuddhiyā: means “for the purification of beings.” All human beings and other beings who are not yet Arahants have minds that are defiled by greed, hatred, delusion, conceit, jealousy, pride, avarice, contempt, wrong-views, and many other kinds of mental impurities. It is these mental impurities that prevent us from seeing things as they truly are. Although we may be aware of these mental impurities within us, it is difficult to remove them. The impurities that we are not even aware of are even more difficult to remove.

Soka: means grief, and paridevānaṃ means lamentation or weeping. When living beings have to face physical and mental pain caused by injury, disease, loss of loved ones, status, or precious possessions, blame and criticism, etc., they grieve and lament because they are not yet free from attachment to pleasure and aversion to pain.

Dukkha: means physical pain, domanassa means mental pain. Atthaṅgamāya: means extinguishing. In Pāḷi, the setting of the sun is referred to as “suriya-atthaṅgama.” In a hot country like Bihar in Northern India, where the Buddha mostly lived and taught, the sun is very hot and oppressive. When the sun sets, therefore, it is a great relief, unlike in cold climates where sunshine is delightful. All living beings recoil from pain, and no one wants to be sad. For beings who delight in pleasure and happiness, pain and sorrow are oppressive.

Ñāyassa adhigamāya: means “attaining the right method.” Learning to meditate is similar to learning to skate or ride a bicycle, but much more difficult. When you are learning some new skill like skating or cycling, you keep getting it wrong, and keep losing your balance. Keeping the mind fully aware of the realities arising and passing away in the present moment is a skill that takes a lot of training and self-discipline. All too often, the mind wanders and gets lost in conceptual thought. It roams to the past and future, delighting in memories, plans, or speculations.

Thinking is not the right method — thinking is a mental process that a meditator must be mindful of to understand its true nature. It is unnecessary and impossible (except in deep absorption) to stop thinking. If you have eyes you will see, if you have ears you will hear, and if you have a mind you will have thoughts. The right method is to be mindful at the moment of seeing, hearing, smelling, tasting, touching, or thinking. This awareness of whatever mental or physical phenomenon is arising in the present moment is right-mindfulness, which leads gradually to understanding things as they truly are.

Yadidaṃ cattāro satipaṭṭhānā: means, “that is the four foundations of mindfulness. The introduction makes it clear that the only way to overcome suffering is to cultivate and establish mindfulness. The discourse continues by elaborating on these four foundations of mindfulness.

Contemplation of the Body

Contemplation of the Body

What are these four foundations of mindfulness? They are: the body, feelings, thoughts, and mental objects. The chapter on mindfulness of the body starts with the section on mindfulness of the respiration (ānāpānasati), and continues with sections on mindfulness of the four postures (walking, standing, sitting, and lying down), clear comprehension of daily activities, perception of repulsiveness of the body parts, analysis of the four elements (earth, water, fire, and air), and the cemetery contemplations on dead bodies.

A meditator does not need to practise all of these, but should choose a method suited to his or her temperament. The discourse was delivered for the benefit of a large number of monks from different groups who had already been meditating in the forest using different meditation objects for contemplation as instructed by their teachers. The Mahāsi Sayādaw taught the method called “Analysis of the four elements” (dhātu-manasikāra). When sitting, the meditator begins by observing the element of motion (vāyo dhātu) in the rising and falling movements of the abdomen while breathing in and out. The air element manifests as pressure or movement, the earth element manifests as hardness or softness, and the fire element manifests as heat or cold.

Where should one meditate? The discourse advises, “Having gone to a forest, to the root of a tree, or to an empty place.” An experienced meditator may be able to maintain mindfulness anywhere, even in a crowded or noisy place, but it is advisable to choose a quiet place where one will not be disturbed. To develop concentration and mindfulness takes a lot of time and effort, if there are too many distractions one will be easily discouraged, so one should go to a meditation centre or monastery where conditions are more conducive to the development of concentration.

How should one meditate? The discourse says, “Ardent (ātāpī), clearly comprehending (sampajāno), and mindful (satimā).” The meaning of “ātāpī” is with resolute, courageous, and strenuous effort to overcome all obstacles that arise. If one allows the mind to roam freely it will go wherever it likes, following sensual thoughts, dwelling on negative emotions, and so forth. If a meditator tries to restrain the mind and limit attention to only a few simple objects in the present moment, the untrained mind rebels and becomes stubborn. One must follow the teacher’s instructions to discipline this rebellious mind and so overcome obstructions such as physical pain, drowsiness, restlessness, and doubt.

A meditator should behave very differently to an average person. He or she should move slowly and gently, speaking very little or not at all. Whatever is done, should be done only after reflection, and it should be done clearly comprehending that one is doing it and why — not flustered, busy, or confused like an unmindful person. The meditator’s attention should be directed inwardly — that is he or she should be mindful of his or her own body and mind. One cannot be mindful of the past or future, it is only possible to be mindful of the present moment. Even if one remembers something done in the past, or plans to do something in the future, the present reality is just a mental process of remembering or planning. A meditator should be mindful of such mental processes as they occur, if there are no such thoughts, he or she should be mindful of the body in the immediate present.

To make this clearer, let’s give a practical example. Suppose that, while sitting and observing the rising and falling movements of the abdomen, the meditator feels an itch on the forehead. An unmindful person would simply scratch it at once. A meditator should not just react. First, he or she should be mindful of the itching sensation and investigate it, observing it until it disappears. If it does not disappear, but only increases and becomes unbearable, then the meditator may scratch it, but in doing so should be mindful of, and acknowledge, the intention to lift the arm. While lifting the arm very slowly, the meditator should keep observing both the intention and the movement. On touching the forehead, know and observe the touching and the scratching movements. Then, on returning the arm to its former relaxed position, be mindful of each and every movement. This is the meaning of “clearly comprehending and mindful.” Nothing whatsoever should be done without mindfulness. If a meditator becomes forgetful and fails to be mindful of any movement, he or she loses his or her life. That is, he or she is no longer a meditator, but just an ordinary unmindful and confused person.

Why should one meditate? To understand things as they truly are. Mindfulness is established to the extent necessary for knowledge and insight, so that one dwells detached and clings to nothing. If one is unmindful, then one does not know objects as they really are. Due to contact with any sense object at one of the six sense bases (eye, ear, nose, tongue, body, or mind), feeling arises. If one is unmindful of the feeling, then craving arises. If one is still unmindful of the craving, then attachment arises, then becoming or striving to obtain, keep, and enjoy that object, or — if it is unpleasant — to dispel and destroy it. That striving is kamma, which leads to birth and death. Thus the whole cycle of suffering and rebirth continues without any end in sight.

Contemplation of Feelings

Contemplation of Feelings

The second chapter of the discourse deals with the contemplation of feelings (vedanānupassanā). As noted in the preceding paragraph, feeling is an important link in the cycle of dependent origination that drives the cycle of suffering. Living beings are easily led here and there by feelings, just as a bull is easily led here and there by means of a rope attached to a string through its nose. We like pleasant feelings and recoil from unpleasant feelings. Neutral feelings do not interest us. A meditator should be mindful of all feelings that arise, whether they are physical in origin or mental, whether they are gross or subtle. Not all feelings are detrimental. If a meditator gains some concentration, he or she may enjoy very delightful feelings as a natural result of the absence of mental defilements. Such feelings may encourage a meditator to make more strenuous efforts to reach higher stages of insight. However, if the meditator is unmindful of these very pleasant feelings, and gets attached to them, then progress will stop. When the feelings disappear, the unmindful meditator may get discouraged and give up. At certain stages of insight, a meditator may experience considerable pain and discomfort, or unfamiliar feelings that are disconcerting. If the meditator is not mindful of these feelings, he or she is unable to progress. To progress without interruption, the meditator should just be mindful of all feelings as they occur, maintaining objectivity and equanimity.

Contemplation of Thoughts

Contemplation of Thoughts

The third chapter deals with mindfulness of thoughts (cittānupassanā). Some who are new to insight meditation have the misconception that to meditate one must stop thinking. It is not necessary, nor is it even possible for most meditators. Discursive thought will stop only in deep states of concentration. For the average meditator, thoughts will continue to come and go even after many weeks or months of uninterrupted meditation practice. The task of the meditator who is striving for insight is to know these thoughts as they really are in the present moment, not to make them go away, but to understand their true nature. A lustful thought must be known as it is. An angry thought must be known as it is. A deluded thought must be known as it is, and so on. Whatever kind of thought arises — whether it is beautiful or ugly, selfish or altruistic, it should be known clearly as a mental process.

Contemplation of Mental Objects

Contemplation of Mental Objects

The fourth chapter deals with mindfulness of mental objects (dhammānupassanā). This chapter is divided into five sections:

1. The Five Hindrances

When a meditator strives to develop mindfulness and concentration, these five mental obstacles will arise when mindfulness is weak. Sensual desires such as memories of sensual pleasures enjoyed in the past, or plans and fantasies about future enjoyments. When pain or noise, heat or cold, hunger and thirst, biting insects, or other irritating things interrupt a meditator’s concentration, he or she may become angry or annoyed. This aversion or ill-will is the second hindrance to concentration. When effort is too weak, the meditator will become drowsy and want to take a break or sleep. When effort is too strong, but concentration is weak, a meditator becomes restless and cannot maintain the same posture for long. Lastly, the meditator may entertain doubts about the method, the teacher’s ability, or his or her own ability to make progress.

These hindrances are perfectly natural. They are not an indication that something is wrong. On the contrary, they are a sign that the meditator has been making some effort to develop concentration. If a so-called meditator just does whatever he or she wants to do, changing posture or taking a break at the first sign of difficulty, the hindrances will not be obvious. Any fool can sit and day-dream all day long, but to meditate seriously with a sincere desire to gain insight requires both knowledge and wisdom. Acquiring a basic knowledge about meditation is not very hard, one can read a few good books, or listen to the teacher’s instructions, but to gain wisdom and skill in meditation takes persistent effort to overcome the five hindrances, whenever they arise.

2. The Five Aggregates

2. The Five Aggregates

These are physical phenomena, feelings, perceptions, mental formations, and consciousness. A meditator should know about the arising and passing away of these mental and physical phenomena. For example, when the eye and a visible form make contact, seeing arises. Dependent on whether the perception of the object is beautiful or ugly, feeling arises — whether pleasant, unpleasant, or neutral. A pleasant feeling tends to give rise to craving, whilst an unpleasant feeling tends to give rise to aversion. Following on from that craving or aversion, mental formations (volitional activities) such as planning to obtain or get rid of the object may follow. A meditator should endeavour to be mindful of this entire process, to understand the process and purify the mind from mental defilements.

3. The Six Sense Spheres

3. The Six Sense Spheres

The eye and visible objects, the ear and sounds, the nose and odours, the tongue and tastes, the body and sensations, the mind and ideas. The meditator should know all of these as they occur in the present moment to understand how fetters such as attachment and aversion arise and obstruct progress in meditation.

4. The Seven Factors of Enlightenment

4. The Seven Factors of Enlightenment

These are mindfulness, investigation, energy, joy, tranquillity, concentration, and equanimity. As the meditator continues to make strenuous efforts to overcome the five hindrances, and to clearly know all mental and physical phenomena in the present moment, the mind will gradually become purified. Whenever there are no mental hindrances then these seven factors of enlightenment will begin to manifest. The meditator will become very enthusiastic about the practice, finding joy and serenity from observing the realities in the present moment. Mindfulness and concentration will be keen. Instead of dwelling in aversion to pain and discomfort, or getting excited by pleasure, if any sensations arise, the meditator will investigate them with equanimity.